In the immediate aftermath of the arson attack on Mississippi’s largest synagogue, there were calls for donations to help them replace their lost Torah scrolls, presumed lost in the fire. And even though later reports said that some of the scrolls had been saved, including the one that survived the Holocaust, I was intrigued by the power a Torah scroll seemed to hold over the Jewish imagination. The fact is, in order to have a congregation, you need ten people and a Torah scroll; you don’t need a building. I wasn’t surprised by the idea that the Torah holds value; the Hebrew Bible overall is seen as the word of God, after all. But the sacredness of the scroll itself, as an object, has always confused me. Aren’t we expressly prohibited from worshipping images of God (idols/statues/graven images, etc.)? Shouldn’t that mean we would avoid worshipping proxies too?

The prohibition against worshipping idols, or any other physical representations of God, was meant to separate out the Ancient Israelites from their polytheistic neighbors, who prayed to many different idols as part of their daily lives. It was also meant to teach us that God is something other than human, other than animal, other than anything that can be represented in a concrete way. And yet, we have all of these objects – the Torah scroll, the mezuzah, the Shabbat candles, the ark that holds the Torah scrolls – that act as supports, like a child’s pacifier or teddy bear, to fill the missing space.

We don’t do a weekly Torah service in my congregation, unless there’s a bar or bat mitzvah to celebrate, so most of my recent experiences with the Torah service come from singing with the choir on the high holidays. The choir has specific songs to sing for the two Torah processions, before and after the reading of the text, and I have always stood with the rest of the choir, turning like a sun dial to follow the Torah on its journey. I didn’t even realize I was doing this, until I returned from Israel with stories of the women at the Western Wall backing away so as not to turn their backs on the wall as they left, and the younger rabbi at my synagogue said that we do the same thing with the Torah, following it with our eyes and never turning our backs on it. And I realized that I must have done this hundreds of times, without realizing it and without knowing why. It reminds me of stories about Crypto Jews who, generations after converting to Catholicism, still lit Shabbat candles in the closet each week, without knowing why. There are still so many things like this, both in Jewish practice and in my life overall, where I do what I’m trained to do, what feels “normal” to me, without knowing why, and without consciously choosing to do it. And I thought I should take a look at it.

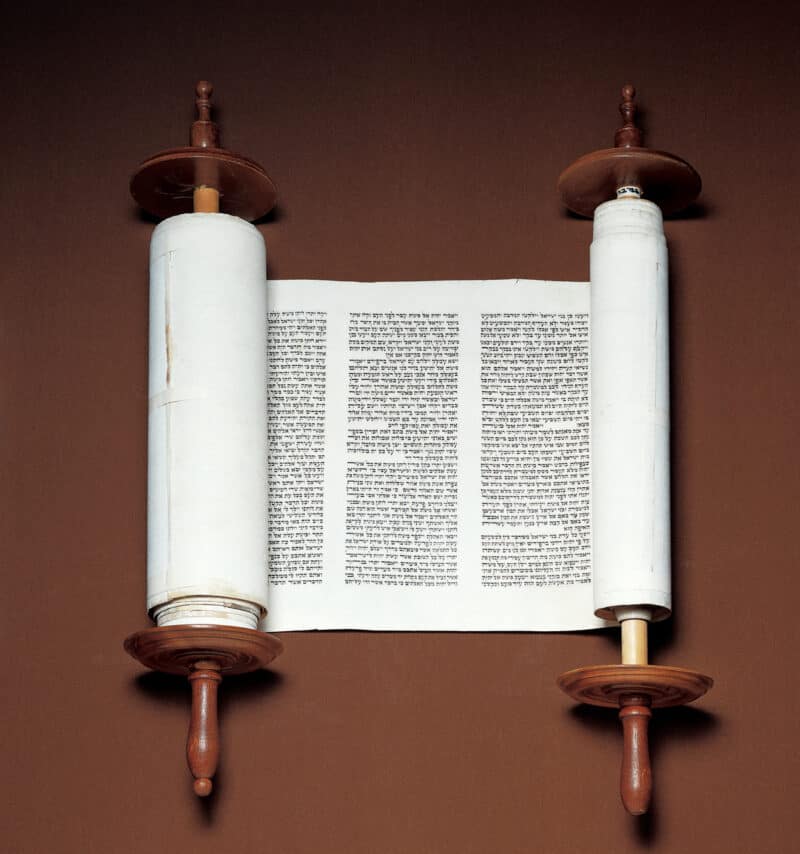

Every Torah scroll is written on specially prepared animal skins, using hard-to-find ink, by a scribe who has been trained for years (often after finishing rabbinical training as well), and each parchment (piece of animal skin) is then carefully sewn to the next until the whole scroll is attached to wooden rollers. The Torah scroll includes only the first five books of the Hebrew Bible (the prophets and writings don’t get the same treatment), and the scribe is required to copy it exactly, including the mistakes that have been collected over time (letters that seem to have been written incorrectly, words that no one knowns the meaning of after so much time). In Ashkenazi synagogues (Jews of Eastern European descent), the Torah is then covered in a velvet dress, with silver crowns and a breast plate for adornment. In Sephardi synagogues (Jews of Middle Eastern and Spanish descent), the Torah scroll is often kept in a metal or silver (bejeweled) container, almost like armor.

There’s pomp and circumstance to the Torah service itself, especially on Shabbat and holidays, as the Torah is taken from the ark, placed gently in someone’s arms and paraded down the aisle of the sanctuary. There is even a custom of kissing the Torah as it passes by. Some people kiss their prayer book, or Tallit (prayer shawl), and then touch that to the Torah, and some touch the Torah with their prayer book or Tallit and then kiss that, to bring the holiness of the Torah to their own lips.

During Covid, most people stopped kissing the Torah for fear of spreading germs, and that reminded me of the sermon my childhood rabbi gave at my brother’s bar mitzvah. This was during the height of the AIDS epidemic, when there was a lot of panic and not a lot of clear information about how the disease was spread, and our rabbi decided to make his sermon about the risk of spreading AIDS through kissing the Torah. He didn’t talk about the pain of those in our congregation who might be suffering with AIDS, or losing family members to the disease, nor did he discuss the incomplete (at that time) science around transmission risk, instead, he focused on the “disgusting” habit of kissing the Torah and managed to insinuate that there was some connection between my brother, who was carrying the Torah for the day, and the transmission of AIDS.

My thirteen-year-old brother was too busy trying to remember his Torah portion, and say hi to his friends in the sanctuary, to pay much attention to the rabbi, Thank God, but the sneer on his face and the anger he had towards my father (for challenging his religious authority, not for being an abusive son of a bitch) stuck with me.

I don’t know if I stopped kissing the Torah because of that sermon, or if it was just part of my overall discomfort with the choreography of prayer and being told what to do, but it worries me that I could still be reacting to that old slight, even unconsciously, rather than acting out of real understanding and deliberate choice. I also don’t bow when we are supposed to bow, and I don’t shake the lulav and etrog on sukkot, and I don’t kiss the mezuzah on the front door of my apartment, though I do make sure to have one. But I always turn my body to follow the path of the Torah on its journey around the sanctuary, sometimes even standing on my tippy toes to see the Torah over the crowd, as if the Torah scroll is a member of the latest boy band, and we are all tripping over each other just to touch his sleeve. But the reality, for me, is that the Torah scroll, and the ark, and the Shabbat candles, and many of the other ritual objects that are so familiar to me from a lifetime of use, offer me some kind of comfort; maybe simply because there’s value in having an object to hold my awe, especially when the only other container available, God, is theoretical, or at the very least, untouchable.

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?

I remember my childhood friend Michael telling me about kissing his prayer shawl in leu of kissing his temple’s Torah scroll. I believe this was after his Bar Mitzvah. He also remembers always facing the Torah when it was carried. (Our friendship happened during the 1960s through early 1970s while we attended the same public schools.)

There’s something magical about having these shared memories with people I don’t even know.

Fascinating post. I learned a lot.

Thank you!

(It’s funny how similar we are yet we’ve never met.)

Thank you for sharing all that you’ve learned!

Thank you! It’s really comforting to know you’re there.

😊

Reviewing what we do automatically and what we resist doing–and the reasons behind them–can be helpful to achieve greater freedom. The unexamined life…

Thanks for the reminder to pay more attention to my actions/reactions/resistances.

Thank you!

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

That was a great dissertation on the Torah and I learned many things. And I hope you appreciate how hard it was for me not to make a comment li8nking “Crypto” Jews and bitcoin. 😁

I hear you. The favored word used to be Maranos (pigs), so I thought this one was a little better.

I am so late responding, but this reminded me of my Catholic faith. We are taught from a very young age of what to do without much explanation. And then the Church wonders why there are so many questions later on in life when we are old enough to ask and want to know. Great post, Rachel.

My number one job with my students is to encourage them to ask questions (even if I have no good answers for them).

It is our relationship w/ God that matters, not ritual. ❤

This is one of your finest writings, Rachel. It touched me deeply. Thank you.

Thank you so much!

Your comment — “ritual objects that are so familiar to me from a lifetime of use offer me some kind of comfort” — applies across a variety of faith communities. I thought of the Catholic rosary, Orthodox icons, the home Advent candles of various denominations. Since we can’t confront God directly, these objects — special parts of creation — help to mediate his presence to us, and the comfort they provide is real.

There’s something essentially human in that need to touch, see, smell a connecting object.

I also know that to get rid of old, broken Tanakhs, they must be buried, not thrown away. I go to an Episcopalian church, and we have our rituals where certian things are also treated as “holy.” I’ve always thought that it’s because they symbolize G_d or even represent Him.

There’s a whole branch of Jewish history education built out of the documents found in one of those burial caches in Egypt. Different rabbis have different opinions about which documents are sacred enough to require burial, but I know of a lot of people who were asked to allow sacred books to be buried with their loved ones.

Wow, didn’t know about the buried with the loved ones.

Would it be possible to ask… the wearing of wigs by orthodox women. What is the thinking behind it?

Back in high school we had a whole lesson trying to explain the rabbis’ opinions on hair coverings (since many of my classmates planned to cover their hair when they married), but it never really became clear to me. The basic idea is that married women should cover their hair out of modesty, so that other men will not be attracted by their hair. Many women interpret that to mean that they have to wear a hat or a scarf whenever they are around non-family members, but some interpret it to mean that as long as the hair you are showing is not your own, you’re fine. I remember girls who were careful to cover their collar bones, elbows, knees, etc. but would wear skintight dresses, which would seem to go against the spirit of the modesty rules, if not the exact letter of the law.

I think maybe we might watch the Torah being paraded through the sanctuary because it, the Torah itself, is such a significant (whether through indoctrination as a child, or training/belief as an adult) part of our religious life and it’s not every day we get that close to it? And just watching it gives us some of that comfort you mentioned. Or maybe it’s just a nice chance to be able to look around the sanctuary and see what everyone else is up to and if they look bored or not or if they’re paying attention? I attended an orthodox shul for a time when I thought that was what I wanted and the rabbi would position himself in front of the procession as they stepped back up onto the bimah and then bend low, and grasp the Torah on both sides and like a lover, lean in and kiss the fringes of the mantel. I never thought it was odd, he’s the rabbi after all and should know what’s up, but I felt it wasn’t something I shouldn’t be witnessing. I don’t think I like your childhood rabbi.

I like your idea that we follow the Torah in order to get a look at our fellow congregants, because that’s definitely what I do. We have to face forward most of the time, watching the rabbi and the cantor at the front of the room, so it’s finally a chance to see who else is in the room, what they’re wearing, how much they’ve changed since last year, etc.

What beautiful writing, Rachel. This is among your very best. It resonated deeply with me – thank you.

Thank you so much!

My mom was terrified of germs but had a lot of thoughts about perceived lucky rituals, which included kissing the torah. She has passed this down to me, and now my kids and grandkids need to kiss the torah. Not a direct smooch – but a touch with the book and then the book to the lips – hopefully the good luck will supersede the nasty germs! 😉

I never knew there was good luck associated with kissing the Torah. So interesting!

she probably made it up!!!