For years I thought I had a solid draft of the second Yeshiva Girl book tucked away, just waiting for the first book to be published so I could neaten it up and publish it soon after. But last year, when I opened the file on my computer and looked at the draft, I was underwhelmed. It was a mess. There were at least three competing versions of the story running around, all incomplete. I had added to, and revised, the file over the years without remembering most of what I’d done.

“Like I forget that I already ate breakfast?”

Reading through what I had, finally, I realized that I was still undecided about where the book should even be set, in time or space. Parts were set in high school, parts were set in college, parts were set in Izzy’s grandparents’ house, and parts were set in a skating rink.

One of the dangers of writing autobiographical fiction is that it’s hard to know which details from real life to keep, and which ones to change. The second Yeshiva Girl book will have to be even less memoir than book one, because I made such a point of giving Izzy a soft place to land in book one, something I didn’t have in real life.

Happy girl!

I want Izzy to have a better life than I’ve had, with love and children and professional success, but I don’t want to downplay the impacts of trauma, because I know better. I want to find a way to let Izzy struggle, so that other survivors can be validated and recognize their own struggle in hers. I want people to know that child abuse, of every kind, leaves deep scars, and that expecting victims to recover on their own, without support, is unrealistic. That’s just not how humans work. But, I still want Izzy to have a happier life than I’ve had. That’s why I gave her a living grandfather, even though my own grandfather died when I was eight years old. And I want to play that out for her, how having that safe place at age sixteen makes a difference in her life, but also, I want to show that it won’t be a magical cure either.

“I prefer magic, Mommy.”

It feels like there are at least ten ways to write the second book, and I almost need to write out all ten in order to feel like I’ve done the work and gotten as much as I need to get out of the process of writing it. In the end, that’s what I did with the first book. I was satisfied with what was on the page because I’d had the chance to write, and delete, every other possible version of the story.

One of the decisions I have to make is about using flashbacks. I have been told, too many times, about the danger of telling stories in flashback. I had a fiction teacher in graduate school who was fierce about the things we shouldn’t use in our writing. Like, no dreams, no flashbacks, and no stories about girls getting their periods.

I really think the second Yeshiva Girl book would benefit from flashbacks, so that I can set the book further in the future without losing good details from the in-between years. And I want to use dreams. I have found dreams to be incredibly vivid in their ability to show how things feel.

“Like when I catch the squirrel?!”

Also, for my own wish fulfillment, I want Izzy’s father to go to jail, or die, or get some fair comeuppance, because my real father did not. I joke that God sent at least ten plagues his way, but none of them worked. The fact is that he has never acknowledged his guilt, or responsibility, for anything.

“Grrr.”

It’s these endless inner conflicts that keep getting in my way, but they are also the reason why I need to write this book in the first place. I’m just not sure how to speed up the work, so that I’ll still have time to write everything else I need to write before I run out of energy. Or time.

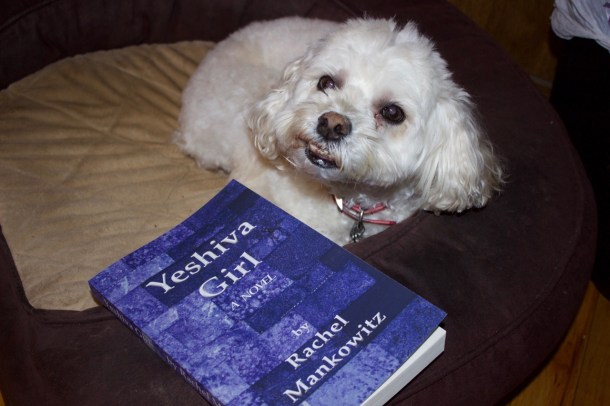

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my Young Adult novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?