On October 7th, 2023, when I started to see media reports of the Hamas attack on southern Israel, I was at a loss – I had no frame of reference for what I was seeing. I knew this was something different from previous terrorist attacks or rocket strikes, but I didn’t know what to compare it to. Early on, I heard some people reference the surprise of the Yom Kippur War, because the fiftieth anniversary of that war had just passed, but those comparisons faded quickly. Then there were the voices calling October 7th Israel’s version of September 11th, but 9/11 didn’t involve hand to hand combat, or rape, or children, and, fundamentally, the world wasn’t as horrified by October 7th as they were by 9/11. And then people said, over and over again, that this was the worst loss of Jewish life in a single day since the Holocaust, as a way to capture the overwhelming shock and grief of the attack; but comparing October 7th to the prolonged and systematic killing of six million Jews (and many millions of others), over the course of years, and across many borders, just didn’t seem helpful to me, and didn’t offer me any idea for how to cope with the horror, or how to respond to it.

And then the word pogrom started to be used, but it didn’t resonate for me at first, either. The word pogrom came originally from Russian, meaning “to destroy, to wreak havoc, to demolish violently,” but historically it has referred to acts of anti-Jewish violence perpetrated by civilians and supported by the military, in Eastern Europe, between about 1880 and 1920. And, at least in my mind, a pogrom was supposed to be about the dangers of being a minority in a world where the majority hates you. Except, for a lot of Jewish people, and not just Israelis, this did feel like a pogrom, and I wanted to understand why.

The thing is, while Jews are the clear majority population in Israel, they are surrounded by an Arab world that is majority Muslim, and the Palestinian cause has often been supported financially, politically and militarily by the surrounding Muslim countries, so the question of who is in the minority and who is in the majority depends on how closely you focus in or how widely you zoom out.

Some Jewish media outlets mentioned the 1903 Kishinev pogrom in particular, early on in the coverage of October 7th, so I decided to do more research to see if I could understand the comparisons.

The Kishinev pogrom took place on April 19-21, 1903, Easter day, in Kishinev, then the capital of Bessarabia in the Russian Empire (now Moldova). The attacks began after church services on Easter Day, which was also, maybe more significantly, the last day of the Jewish holiday of Passover. During the pogrom, 47 to 49 Jews were killed, 92 were severely injured, 700 houses were damaged, hundreds of stores were pillaged, and 600 women were raped; while the police and army did nothing.

Leading up to the attacks, the most popular Russian language newspaper in Kishinev was regularly publishing headlines like: “Death to the Jews!” and “Crusade against the hated race!” So that when a boy was found murdered in a town twenty-five miles away, and a girl committed suicide by poison and was declared dead at a Jewish hospital, the newspaper had a ready audience for its insinuations that both children had been murdered by the Jews so that their blood could be used to make matzo for the coming Jewish holiday of Passover (a bizarre blood libel that keeps coming up throughout history to incite violence against Jews, despite the fact that matzo is made of only water and flour, and blood is strictly forbidden in Jewish dietary laws).

On April 28th, the New York Times reprinted a Yiddish Daily News report smuggled out of Russia that described the pogrom:

“The mob was led by priests, and the general cry, ‘kill the Jews’ was taken up all over the city. The Jews were taken wholly unaware and were slaughtered like sheep…babes were literally torn to pieces by the frenzied bloodthirsty mob. The local police made no attempt to check the reign of terror. At sunset the streets were piled with corpses and wounded.”

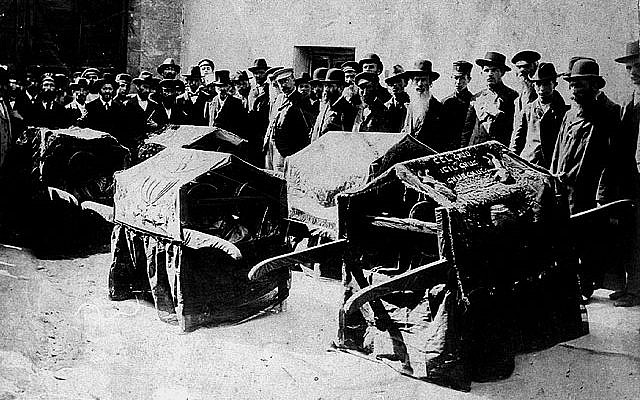

Many pogroms had taken place before this one, but the graphic descriptions, and especially the photographs, of the Kishinev pogrom were sent around the world and made a deep impression, especially on American Jews who began organizing financial help for the Jews of Kishinev to emigrate to America and Palestine. The danger to the Jewish population of Europe was convincing to most people, though the Russian ambassador to the United States at the time tried to deny that the attacks had anything to do with anti-Semitism, blaming it on Jewish moneylenders upsetting the local peasants with their corrupt business practices.

But even more than the news reports and the photographs, the biggest impact the Kishinev pogrom would have on Jewish history came in the form of a poem.

Chaim Nachman Bialik, a journalist, poet, and publisher, was commissioned by the Odessa Jewish Historical Commission to travel to Kishinev and collect testimonies from the survivors of the pogrom. Bialik, who later came to be seen as Israel’s national poet, with his poems taught across the Israeli school system, was an early advocate for Zionism and the need for a new kind of Jew, a stronger, bolder Jew who wouldn’t be so vulnerable to antisemitism.

As he walked through Kishinev and listened to the survivors of the pogrom he began to form an idea for a long poem in Hebrew that would be published in 1904, meant to wake Jews up to the impossibility of life in the diaspora, called “In the City of Slaughter.”

“Do not fail to note, (he wrote)

In that dark corner and behind that cask,

Crouching husbands, bridegrooms, brothers peering through the cracks,

Watching their wives, sisters, daughters struggling beneath their bestial defilers,

Suffocating in their own blood,

Their flesh portioned out as booty.”

Bialik’s vision of the diaspora Jew’s weakness, and his willingness to blame the Jewish men for the rapes of their wives and daughters, became a rallying cry to find a place where Jews could be in the majority and therefore able to defend themselves. He, significantly, left out any references in the poem to the fact that local Jews had tried to defend themselves, but had failed because police dispersed those Jews attempting to defend Jewish homes and businesses, while allowing the rioters to go unchecked (Russian courts later used those attempts at self-defense to suggest that it was actually the Jews who struck first, and were therefore responsible for the riots that killed them).

But even if Bialik had acknowledged those attempts at self-defense, the lesson would still have been the same: life in the diaspora, in the minority, isn’t safe.

“Of murdered men who from the beams were hung,

And of a babe beside its mother flung,

Its mother speared, the poor chick finding rest

Upon its mother’s cold and milkless breast;

Of how a dagger halved an infant’s word,

Its ma was heard, its mama never heard.”

As a modern day Jew living in America, when I read this poem I got really angry, at Bialik, for the way he blamed the victims of the atrocity. It felt like identification with the abuser, in today’s therapy speak, but at the time it was galvanizing and convinced a lot of people that Zionism was the only answer for Jewish survival.

The word diaspora is often used as a stand-in for the Hebrew word Galut, which means “exile.” The idea is that after the destruction of the second temple in Jerusalem, in 70 CE, God exiled the Jews from the land of our ancestors, for our sins. This is how we are supposed to see our lives in the diaspora, as outside of God’s favor. But we don’t, or, I don’t. (This belief that we are in exile because that’s how God wants it, is why certain Chasidic groups are anti-Zionist. They believe we have no right to return to Israel until God brings us back there, in the time of the messiah). The Zionist cry was, let’s not wait for God’s permission to go home anymore, let’s not wait for the messiah, because if we wait too long we will be annihilated.

There was actually a second pogrom in Kishinev two years later, killing nineteen Jews, as part of a huge wave of pogroms across the Russian Empire during which 200,000 Jews were murdered in an estimated 600 different attacks on Jewish communities. But it was the first Kishinev pogrom that was remembered, and Bialik’s interpretation that lingered.

Interestingly, at the same time that Bialik was teaching the Jews about the power of a poem to inspire action, Pavel Krushevan, the publisher of that Russian newspaper in Kishinev that had incited the pogrom in the first place, had also learned an important lesson: incitement works. Within months he had published The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a fictional account of Jewish leaders plotting to control the world, presented as if it were true. This book later spread around the world, teaching anti-Semitism to an ever wider audience. Hamas even refers to elements of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion in their charter.

As I continued to read Bialik’s poem, and the details of the Kishinev pogrom itself, it became clear that even though some of the circumstances of a pogrom didn’t fit what happened on October 7th, many of the victims of October 7th felt the same powerlessness of the Jews in Kishinev, in large part because of the failure of the Israeli government to prevent the attacks, or to intervene to protect them in time, and, all over again, the lessons of Kishinev, especially the need for muscular self-defense, were back in the forefront of people’s minds.

The most penetrating message of the poem, for me, is Bialik’s anger at the Jews of Kishinev for not being angry enough.

“Turn, then, thy gaze from the dead, and I will lead

Thee from the graveyard to thy living brothers,

And thou wilt come, with those of thine own breed,

Into the synagogue, and on a day of fasting,

To hear the cry of their agony,

Their weeping everlasting.

Thy skin will grow cold, the hair on thy skin stand up,

And thou wilt be by fear and trembling tossed;

Thus groans a people which is lost.

Look in their hearts, behold a dreary waste,

Where even vengeance can revive no growth,

And yet upon their lips no mighty malediction

Rises, no blasphemous oath.”

The story of Kishinev, and the shame of it, had largely faded from the minds of American Jews by October 7th 2023, to the point that I don’t think it was even mentioned at my orthodox Jewish high school, where we studied Jewish history as part of our daily coursework, because it didn’t resonate for us, here, where, even now, despite growing antisemitism, and incidents of horrific violence, we feel at home in the diaspora. We feel safe. But in Israel, where the philosophies of Bialik and the other early Zionists are well-known, and where the population is largely the descendants of refugees from the diaspora, or the relatives of those who did not survive, feeling safe is more elusive.

To many, and maybe most, Israelis, the horror of October 7th was that even the new, strong, brave, well-armed Jew couldn’t prevent a Kishinev. And if the New Jew wasn’t enough, what would be?

Interestingly, while many Jews continue to see Israel through the lens of the Holocaust, and the pogroms of Eastern Europe, the Arab world has been taught to believe that these things never actually happened. Mahmoud Abbas, the “moderate” President of the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, has consistently misrepresented, minimized and even denied the Holocaust. He has said that Hitler killed European Jews not because of anti-Semitism but because of the Jews’ “social functions” in society, such as money lending (just as the Russian Ambassador to the United States had said about the Jewish victims in Kishinev). In his doctoral thesis, written at a Russian University, Abbas argued that the Zionists had even colluded with the Nazis, agreeing to the extermination of the Jews of Europe in order to convince the world of the necessity for a Jewish state in the land of Israel. He has said that it’s possible that 6 million Jews were killed, but it’s also possible that it was less than a million. And, while he’s denying and minimizing the Holocaust on one hand, he’s also accusing Israel of committing “fifty holocausts” against the Palestinians on the other hand. And he’s not alone. Holocaust denial is rampant and normalized in the Arab world, where Mein Kempf and Protocols of the Elders of Zion have been widely published, and using the language of the Holocaust against Israel (calling them Nazis, accusing them of genocide, etc.) continues to be a common rhetorical tool.

And the thing is, if you’ve been raised to believe that the Holocaust was at the very least exaggerated, if not created from whole cloth, for the sole purpose of stealing Palestinian land in 1948, no wonder you would hate the Jews and think Israel has no right to exist. The fact that these ideas are so easily disproven is maddening. The Holocaust was minutely catalogued by the Germans themselves, similar to how Hamas documented the October 7th massacre with their Go-pros, and yet many Palestinians, and some of their supporters in the Arab world and in Europe and America, have even said they believe that October 7th was not only not as bad as it has been portrayed, but that it was perpetrated by the Israeli army itself.

The Kishinev comparison has been helpful for me in a lot of ways, especially in understanding the Israeli certainty that the right response to the attacks was overwhelming force, but there’s one overriding reason why the analogy doesn’t fit: the hostages. When Hamas militants and their civilian supporters took hostages back to Gaza with them, specifically to instigate a bloody ground war with Israel in order to turn world opinion against the Jews, they also, intentionally or not, created a double bind for Israelis that would create a whole new kind of horror; the choice between saving the hostages, by ending the war now and releasing all terror suspects along with all of the other Palestinian prisoners from Israeli jails, versus continuing the war so as to prevent future attacks and to prevent future hostages from being taken, is an impossible one.

The horror of knowing that so many hostages are still being kept in the tunnels of Gaza, and that the world stopped thinking about them a long time ago, is unbearable. It can’t be understood by a comparison to any other event; it refuses to be categorized or contained or ignored.

So here we stand, with the Palestinians in a constant state of Nakba, or catastrophe, ever since the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, believing that their land was stolen by vicious invaders who constantly lie about their origins and intentions, and Israelis constantly afraid of another Kishinev and, inevitably, another Holocaust.

I don’t know how we move past these narratives to help us see a new way forward, but maybe a new poem could be written, one that addresses the narratives of both peoples, or rather of the many different people within the larger mosaic of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and maybe that new poem could imagine a future where something other than violence prevails. I wouldn’t know how to write that poem, or who might have the skill and perspective and confidence to try, but I’d like to believe it will be possible. One day.

The City of Slaughter https://faculty.history.umd.edu/BCooperman/NewCity/Slaughter.html

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my Young Adult novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?