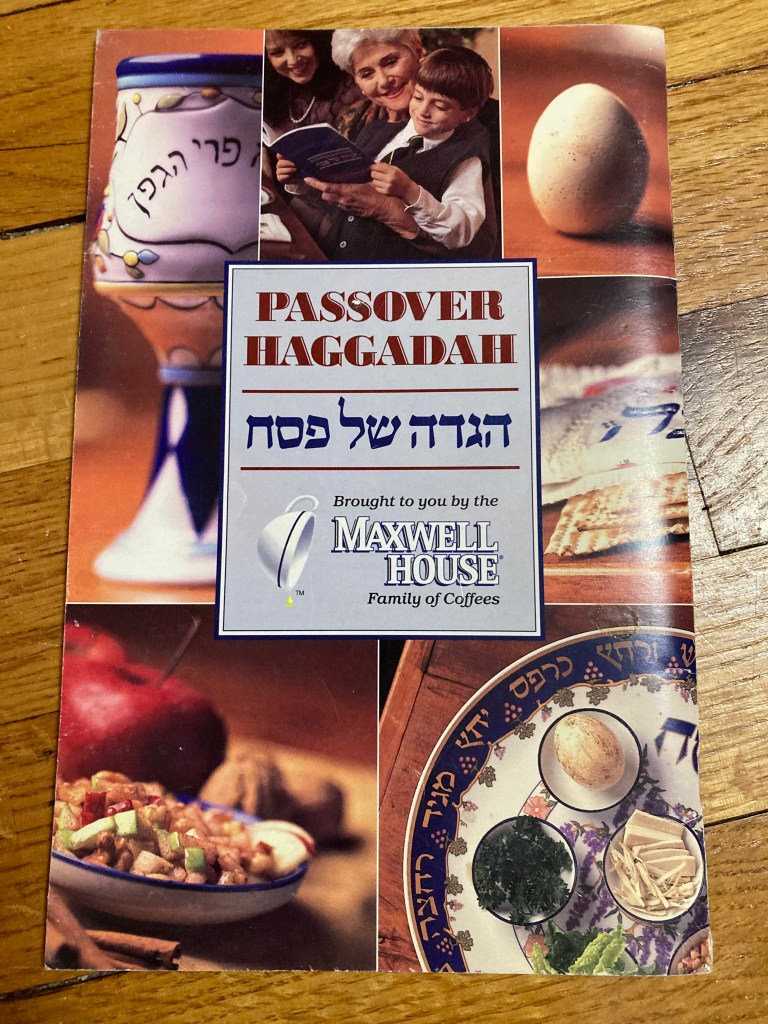

As part of our preparation for Passover this year, my students and I looked at different elements of the Haggadah, the book used to guide the Passover Seder. We tried to figure out the mysteries of the ten plagues (What’s so terrible about frogs? Why do you need Lice and locusts? What does it mean that God hardens Pharaoh’s heart against letting the Israelites go and yet also sends plague after plague to convince him to let them go? Does this mean that God wants to cause Pharaoh pain? And if so, why must all of the Egyptians suffer along with their leader?); and we looked at the objects on the Seder plate (does anyone actually eat the parsley dipped in salt water? Couldn’t we just substitute pickles for the green vegetable and the salt water, all in one convenient package?); and, why is the Seder so freakin’ long?

But the part that always gets to me most is when we read about the four sons (the wise, the wicked, the simple, and the one who doesn’t know how to ask) and how the rabbis recommended we answer their questions.

There are many reasons to find fault with this section of the Hagaddah, but first and foremost my reasons are personal: my father always chose for me to read what the wicked son had to say. He thought it was hysterical that every year he could call me evil in front of guests and get away with it. But having read that passage so many times has focused my attention on the question: what’s so wicked about the wicked son wondering what this whole Exodus story has to do with him?

I’ve seen dozens of revised versions of the four sons: changing it to the four children to include the other half of the population; renaming the wicked son to the rebellious child; and imagining the four children as four parts of all of us.

I actually love the idea that the rabbis thought to add a section to the Hagaddah where we are told to look at the children at the table and try to figure out how to answer their questions. It’s just that the rabbis gave terrible advice, and their method of categorizing the children is both vague and judgmental and still doesn’t really help us figure out what to say to them.

Earlier in the Seder, the youngest child recites the official Four Questions, chosen by the rabbis long ago and usually answered before Passover even begins by your friendly neighborhood synagogue school teacher. Why Matza? Because the Israelites had to rush to bake bread the night they escaped from Egypt and the bread had no time to rise, or because we used to rely on sympathetic magic at this time of year to encourage the harvest, and preventing the bread from rising was a way to reserve all of the fecundity for the crops. Why bitter herbs? Because slavery is bitter. Why dip a green vegetable in salt water? Because the green vegetable (often parsley) represents spring and the salt water reminds us of the tears of our ancestors. Why do we recline at the Seder? Because free people are able to relax while they eat and somehow don’t mind the resulting heartburn.

The recital of those four basic questions is supposed to be the beginning, and not the end, of the questions people ask at the Seder, and in the same way I wish we could portray (at least) four different kinds of children at our Seders in a way that would inspire us to be more curious about the actual children in our lives and to come up with ways to spark their imaginations.

What if instead of labeling the child who agrees with us as wise, and the one who disagrees as wicked, we could listen to them long enough to figure out the who behind the concerns they are bringing up?

In that spirit, I asked my students which children they would choose if they were writing the Hagaddah today, and they had a lot of ideas. They thought about the depressed child and the bored child, the discombobulated child and the hungry child, the happy child and the lonely child, the frightened child and the curious child, the constipated child (too much Matza), the self-absorbed child, and the brave child. And really they could have gone on and on. What they didn’t do was to describe the children in the judgmental and external ways the rabbis had done. They focused on who the child is to him or herself: she feels sad, he feels uncomfortable, she’s shy around so many strangers, and he wants to see what happens if he feeds horseradish to the cat.

The central obligation at the Passover Seder is not to eat Gefilte fish or hide the Afikomen, but to re-tell the story of the Exodus, because we recognize the power of this story to help us find meaning in our lives: to teach us to have hope even in dark times, to learn how to stand up to bullies, to remind us that we can ask for help and that we should help others on the journey when we can. This yearly retelling also teaches us to remember our own individual traumas, and name them, and embrace the ways they have made us who we are today. If we pretend that life is beautiful all the time we won’t search for new ways to solve our problems and will remain stuck in Egypt. The mantra to “never forget” has been associated with the Holocaust in modern times, but the lesson is thousands of years old and stems from the Exodus story and the command to retell it. Our ancestors knew the power of memory and the need for storytelling to help us shape those memories into life lessons.

The Israelites are never portrayed as perfect people in the Hebrew Bible, they are intentionally portrayed as human and flawed so that we can see ourselves in them and learn the lessons they learned from their lives. The four children can be seen as part of this tradition too: the one who complains all the time (Manna? Again?!), the one who is always jealous of someone else’s share (why does Moses get to be in charge all the time?), the one who is afraid to cross the sea (why does everything have to be so difficult?), and the one who has the faith to take the first step and lead the rest to freedom. They are all part of the same whole; they are us.

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my Young Adult novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?