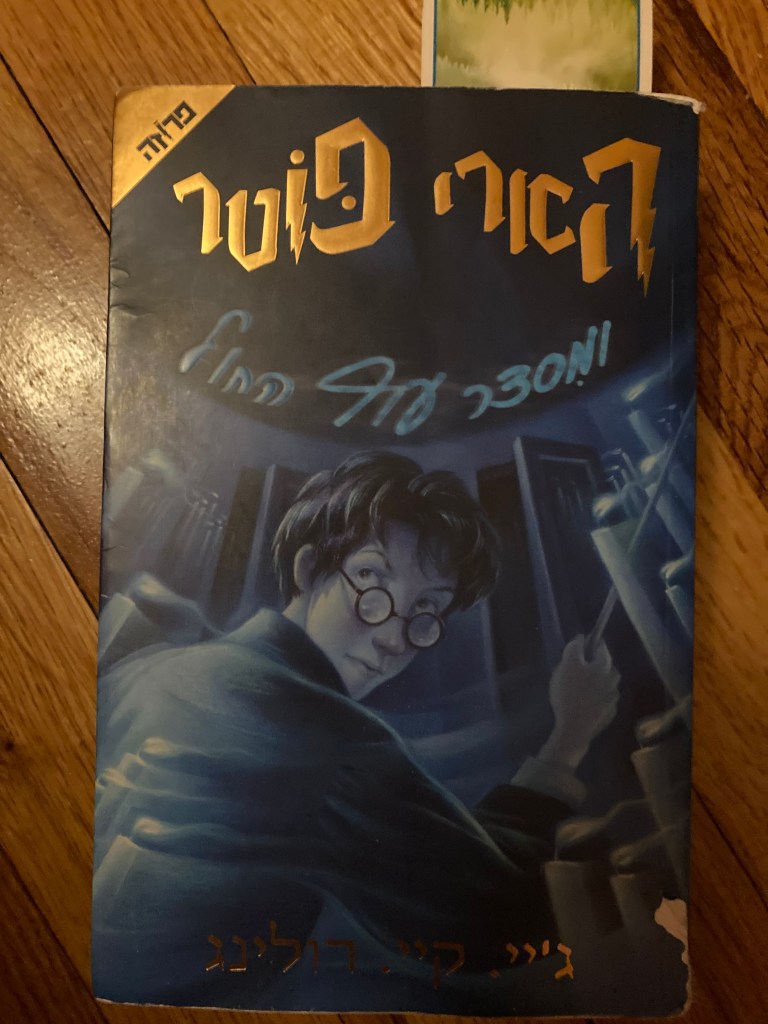

I recently started to read a collection of short stories by Etgar Keret, in Hebrew, as a way to practice my Hebrew reading skills and build vocabulary. I’m generally not a short story reader, but my current Hebrew teacher suggested that short stories would be an easier lift than whole novels, and Etgar Keret is the best-known short-story writer in Hebrew today. The other benefit of reading an Israeli author (rather than an English language book translated into Hebrew, like my Harry Potter books, which I’ve been trying to read for many years now), is that I can learn more about life in Israel while improving my Hebrew. The fact that Keret is so popular in Israel suggests that his work resonates with many Israelis.

Of course, even though the first story in the book (the title story), “Suddenly a knock at the door,” is only 3 or 4 pages long, I managed to fill three pages with vocabulary words to look up on Google Translate; words like “holster,” and “butcher’s knife,” and “avalanche,” are probably not going to end up on my long-term vocabulary list, but “nerves,” and “politeness,” and “boiling,” might be helpful down the road.

The problem is that I found the first story in the collection painful to read, even after getting all of the vocabulary translated. The disconnect between Etgar Keret’s characters and reality, and between his characters and their own emotions and actions, makes it feel like we too, as readers, are in a dissociated state as we follow the story. A number of the stories I’d already read by him, in various classes, involved the need to go to extremes in order to “feel something,” as if his characters are all living their lives in an extended state of post-trauma. There’s also a lot of loneliness in his stories, and an inability for the protagonists to connect to the other people in the world of the story, despite increasingly desperate attempts to do so.

After reading 1 ½ stories, I already needed a break, and I decided to go online to see what other readers had to say about Keret’s work, in English, in case I was missing something in the Hebrew. One reviewer called his stories “a blend of the mundane and the magical,” and many called his style “surreal,” but no one could really explain to me why his writing resonated with so many people, or why Keret himself felt compelled to write this way. And then I found an interview he’d given, where he said that whenever he feels angry with someone and he can’t get past it, he writes a story from their point of view, as a way to put himself in their shoes and try to humanize and understand them. He has, for example, written at least ten stories from the point of view of Benjamin Netanyahu, the seemingly-forever-Prime-Minister of Israel who has moved further and further to the right throughout his time in power. And hearing Keret’s real voice, as opposed to his fictional one, helped me to understand his stories a little bit better. They seem to be, at heart, Keret’s attempt to connect with and make sense of his fellow Israelis, and the disconnect I feel as a reader echoes his own frustration at not being able to do so.

Etgar Keret’s version of Israel is a world filled with missed connections, and deep wounds, and problems that can’t be solved, even though his characters want it to be otherwise; and it’s illuminating to know that many people in Israel find Etgar Keret’s version of their world familiar. Would I have gotten all of that from reading the stories only in English? I’m not sure. The fact is, it was only out of a desire to practice my Hebrew that I was even willing to make the effort to enter into Etgar Keret’s world in the first place. And there’s something to be said for that, for the value of investigating the world through another language and another point of view, in order to see and understand things that are usually out of reach.

One of my classmates in the online Hebrew language school is a native Arabic speaker from Jerusalem. He spent years working in the United States and becoming fluent in English, and now he is back in Israel, learning Hebrew and training to become an English teacher. His goal is to use his English to create a bridge between Hebrew and Arabic speakers, and between Jews and Arabs in Israel. And every time I listen to him talk about his work, I’m inspired to add Arabic to my Duolingo list, but I never do it. In a way, Arabic feels as distant and strange to me as Etgar Keret’s world, but the fact that Hebrew and Arabic come from the same language family and have both borrowed from each other at different points in their development, means there is a lot for me to discover about Hebrew by learning some Arabic. I actually know a bunch of words in Arabic already, because they’ve been borrowed into Hebrew, either with their original meaning intact or with some alterations, but I only know how to read or write them in Hebrew and to go any deeper into the language I’d really have to start with the alphabet, which is all new to me.

I’ve heard from many people, recently, that they would love to be fluent in Hebrew, or any number of other languages, if they could only take a magic pill, or insert a chip into their brains, because the actual work of learning another language is too hard. I’ve always assumed that the reason it was taking me so long to become fluent in Hebrew (or French, or Spanish) was because I wasn’t working hard enough, or I was doing it wrong, but I’m finally starting to understand that while there are some people who are extraordinarily talented with languages, most of us have to work at it, and it takes a long time.

So, I’m continuing to read the Etgar Keret stories, and taking my Hebrew classes, and adding Arabic to my Duolingo list, because I’ve discovered that even if I never become fluent in another language, I’m still learning more than I ever expected to learn along the way, and it’s making my life and my understanding richer, no matter how long the journey takes.

A review: Etgar Keret’s “Suddenly, a Knock on the Door” – Words Without Borders

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?