This past winter and spring, I was busy writing something new. I had wanted to work on revisions for the second Yeshiva Girl novel, which has been in the works for way too long, or add to the draft of the synagogue mystery that I’ve also been mulling over for years, but instead a new story burbled up. By May, I had a 220 page first draft of a novel, tentatively titled Hebrew Lessons, about a young woman who takes online Hebrew classes (like me) and falls in love with her Israeli teacher (that part is fiction. Sorry). It was fun to write and also gave me a chance to think about the relationship between Jews in America and Jews in Israel, which has always been complicated, and has become even more so since October 7th.

The problem is, now that I have to start re-reading the draft and planning revisions, I can’t make myself do it.

While I was writing the first draft I was able to shut out the big, noisy critics in my head, for the most part, with a gentle “Shut the fuck up!” But now that I’m ready for revisions I need to keep the door open to critiques, and the big, noisy, nasty voices in my head keep pushing their way in through the open door.

Even looking in the direction of the manuscript, which is sitting on a pile of books next to my bed, brings up all of the nasties: How dare you write a story with an Israeli character when you’ve never been to Israel? What the hell do you know about love? No agent will touch a book with a Jewish character now, let alone an Israeli! Everything you write gets rejected so why waste your time? Your writing is too serious, silly, sentimental, simple, stupid, etc. You should be ashamed of yourself for thinking your voice even matters. You should be doing something more responsible, selfless, constructive, etc. with your time. If you actually finish the book you’ll have to write query letters and face rejection, and you’ll be embarrassed when people see your imagination written out on the page, like an x-ray of your inner self.

At first I thought I just needed a few weeks away from the book to get some perspective, but then weeks passed and, if anything, the voices got louder, and nastier, and I couldn’t do anything to stop the flood.

Eventually, an image came to mind from the first Superman movie (with Christopher Reeve), where the bad guys (General Zod and his two henchmen) are sentenced to jail and trapped in these flat/see-through boxes where they can be seen, but not heard, for eternity. And I thought, that would be awesome!

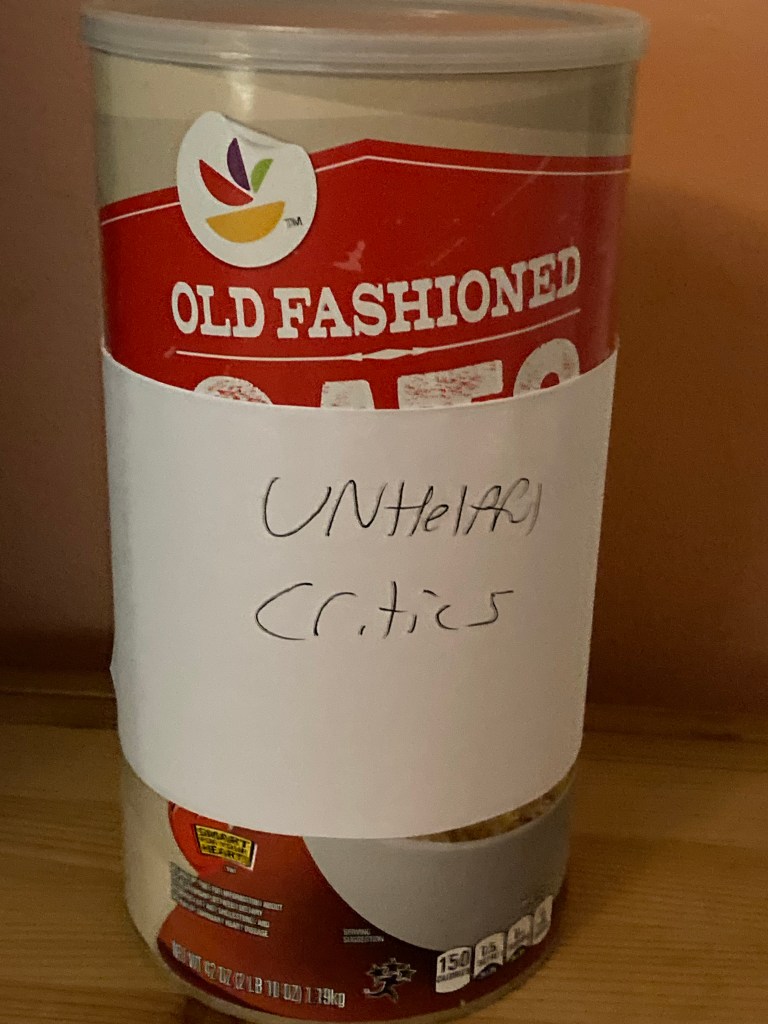

Mom found me a jar (she collects them for art projects) and I labeled it “Unhelpful Critics” and started to fill it with slips of paper slathered with critical messages. But the voices kept coming, threatening to overflow the jar, and my resistance to reading the draft stayed just as strong.

I’m sure that part of the problem is my inability to convince myself that it’s okay to ask to be treated with kindness, so when a critique is hurtful and I want to shove it in the jar, I worry that I’m being too easy on myself and ignoring a painful reality that I really should force myself to face. There’s also the issue that it’s been hard to separate out a specific, technical criticism (the pacing is too fast or slow, the details of the setting are too sparse or vague) from the big bad feelings that stick to every criticism and feel like a punch in the gut. It’s as if the nasty, destructive voices in my head attach themselves to even the mildest suggestions for improvement, and make it all into a toxic mess.

But I really wanted the jar, or anything, to work, so I kept filling out these strips of paper, until I had to graduate to an oatmeal container, and then until I couldn’t capture them in words anymore, but they were still coming, constantly.

It took me too long to start to wonder why all of this pain was coming up around the novel, and yet I’ve been able to write weekly blog posts forever without being swamped this way. And I had to ask myself, why is writing fiction, in particular, bringing all of this up?

I have always loved fiction, writing it and reading it, for the way it can organize reality, and improve on it, and create safer containers for all of the experiences that overwhelm me in real life. But maybe, at least in this case, imagining a better version of my life, and myself, means facing all of the grief I feel that that isn’t my life, and the jealousy I feel that this imaginary young woman gets to live that life. There’s also, interestingly, a deep fear of the unknown, because in living vicariously through her, and facing difficulties and opportunities I’ve never faced, I’m overwhelmed with anxiety about how to solve these unfamiliar problems, in love and life and work. And I feel guilty that I don’t have the tools to protect her from that pain.

I think there’s another aspect to this as well. When I write my short essays I imagine my blog readers, who are so kind and curious and generous, and so much nicer to me than I am to myself, and that allows me to feel safe enough to write difficult things. But when I write longer things, like the novel, or something else that I expect to send out to literary magazines or agents or editors, I hear the cold, dismissive, and destructive voices I’ve faced so many times over the years, in graduate school and beyond, and those voices set off my inner critics and it becomes a wildfire.

Maybe, if I could find a way to think of the novel as a very long blog post, or just imagine my blogging friends as my primary readers, the nasty voices would step aside, or at least quiet down, but I don’t know how to make that switch. If I tell myself that I’m not going to send the novel out to be judged by the industry, then either I won’t believe it, or I’ll believe it and that will set off a whole other kind of grief, because I’m not ready to give up on the possibility of being a successful author, not yet.

But the thing is, I really loved writing the first draft of this book, and I want to get back to that feeling, and I also want to finish the book so I can see if other people like it as much as I do. I feel like just writing this essay has gotten me most of the way there, but I’m not quite there yet, and I’m not sure what else to try.

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my Young Adult novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?