I must have glanced past the listing for 911 in the TV Guide a hundred times without really seeing it, or maybe I assumed it was a documentary show about chasing criminals or something else I didn’t want to watch. But a few weeks ago, I saw a short interview with Angela Bassett (What’s Love Got to Do with It, Waiting to Exhale, How Stella Got Her Groove Back, etc.), about losing her costar in the final episode of 911 for the season, and I got curious. Angela Bassett is on a TV show? And her co-star died? Or just the character he played on the show? I can’t even remember if I saw this information on YouTube or in the “news” on my phone, but I was interested enough to go a-googling and found out that, yes, Angela Bassett has a TV show, called 911, and it had just finished its eighth season, and her husband on the show, played by Peter Krause (Parenthood, Six Feet Under), had been killed off and “everyone” was shocked.

I was intrigued enough to look for episodes of 911 in the Free on Demand section of my DVR, but there were only five episodes available, from the middle of season eight, and I decided that I didn’t want to drop into the show at the last minute with no idea what was going on. I took a minute to be annoyed that the Free on Demand thing has so few episodes available now (it used to have whole seasons and previous seasons), but then I mostly forgot about it. You don’t want me to watch your show? Nu? Fine.

Not long after that, I was looking for coverage of the French Open in the guide on my TV (rather than the hard copy TV Guide that still comes to my house every week), and I checked ESPN and ESPN 2 and the page of channels before and after them, and I noticed the numbers “911” as they passed by. It turned out that WeTV, a channel I don’t generally watch, had a marathon of episodes from 911 all day long, and I thought, eh, why not record a few episodes, and if I’m not interested, I can erase them later.

I set the DVR and then went back to searching for the French Open. Except that the tennis got boring very quickly (I’m not a big fan of clay court tennis, I don’t know why), so I started watching one of the 911 episodes as it was recording, and I was hooked. I raced to set the DVR to record the rest of the episodes in the marathon, and then I spent the next few days watching episode after episode, in between naps. I wasn’t able to start watching from the first episode of the show, or even the first season, so there were a lot of mysteries left unexplained, but I was riveted anyway. Then the next week, I discovered that WeTV does a 911 marathon every Tuesday. So, every week now, I happily spend a couple of days watching a season or more of this show that I didn’t even know existed a few weeks ago.

I’m sure that part of the attraction of this show is that I’m on summer vacation, and with everything going on in the world I’ve needed a good, fictional distraction. But there’s also something about the people that draws me in. First of all, I love the character Angela Bassett plays. She’s a police officer (the 911 call center, the police, and the fire department in Los Angeles are the three focal points of the show), married to a firefighter, and she is never the damsel in distress, but she’s also never made out to be superhuman either. She has her flaws and her strengths, like a real person. Then there’s Aisha Hinds’ character, Hen, a paramedic/firefighter/medical student married to another strong woman (played by Tracie Thoms, from Rent and Cold Case, and a bunch of other things), and I love how these women have created a family together, embracing Hen’s aging mother, mothering an adopted son, taking in foster children and generally being the emotional home base for a lot of the other characters on the show. And then there’s Jennifer Love Hewit, who plays a 911 operator/former nurse/former victim of domestic violence. A million years ago, Jennifer Love Hewit was one of the beautiful up-and-coming actresses in Hollywood, and then she seemed to disappear, or at least I didn’t see her in many things, but now here she is, playing a woman with a lot of resilience and vulnerability, and, maybe most important for me, she’s not a skinny little thing anymore. On this show, women come in all sizes and have real lives, full of love and romance and conflict and drama. Lots and lots of drama. Both the women and the men on this show are portrayed as real people: sometimes confused, always imperfect, but also kind and generous and smart and brave. I love that in a show about unreasonably heroic behavior (and there are some wild storylines that put the heroes in life threatening danger very very frequently), none of the characters is impervious to pain or struggle.

This is not an HBO-type show, where everyone and everything is morally ambiguous; the heroes on 911 are all genuinely heroes and genuinely striving to be better people, though they are often challenged along the way. I’m not a huge fan of all of the gory disasters on the show, and how impossible some of them are (our two heroes go on a cruise to escape their hectic lives and end up being attacked by pirates and almost drowning as the ship sinks into the ocean), and I often find myself covering my eyes during the rescues, just waiting for the worst of it to be over. And, yes, sometimes the plot resolutions on the show are a little too fast, or too simple, for my comfort. But overall, these characters are people who make me feel hopeful about the world, and hopeful about the people who live in it. These people are kind, and funny, and down to earth, and I’m not being asked to identify with bad guys, or to forgive heinous behavior. There’s enough of that in the real world, thank you very much.

But now, a few weeks into my 911 marathon, as I get closer and closer to the current season, where I know ahead of time that one of the main characters is going to die, I’m dreading it. I’ve become attached to these people, and I’ve gotten used to how the characters can put their lives at risk multiple times in every episode and still defy death. Of course, it’s unreasonable to believe that people could go through this many life-threatening events and come out relatively unscathed, but season after season that’s what they’ve been able to do, and the idea that reality is coming to get even my fictional friends just sucks. And yet, I’m still watching, because I care about these people, and because, in a weird way, I feel like I need to be there for them in their time of need. It’s kind of like the way I watched videos of Israelis in their safe rooms and underground shelters during the recent war with Iran, because I felt like if I shared in their struggle I could remove some of the pain, or something.

Now that I think about it, I don’t even know if WeTV will be able to show episodes from the latest season of 911, or if I’ll have to piece the story together from the few episodes available on Free on Demand, but either way I will keep going, and maybe hoping that now that I’m watching the show the outcome will be different. I mean, that’s how the world works, right?

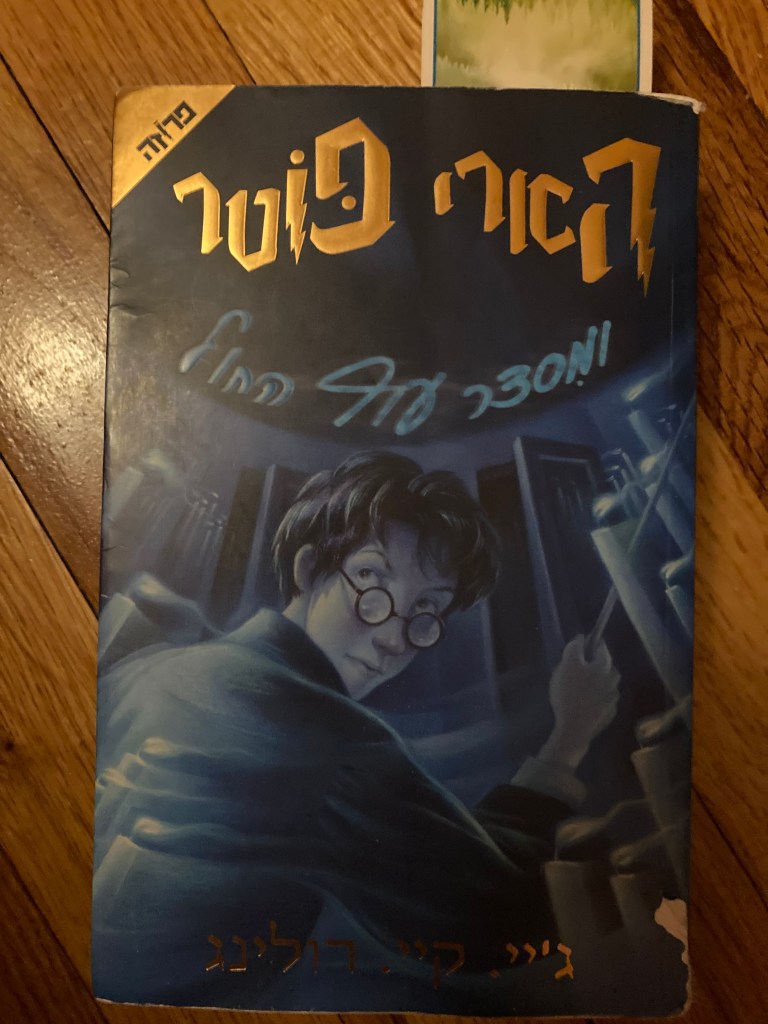

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?