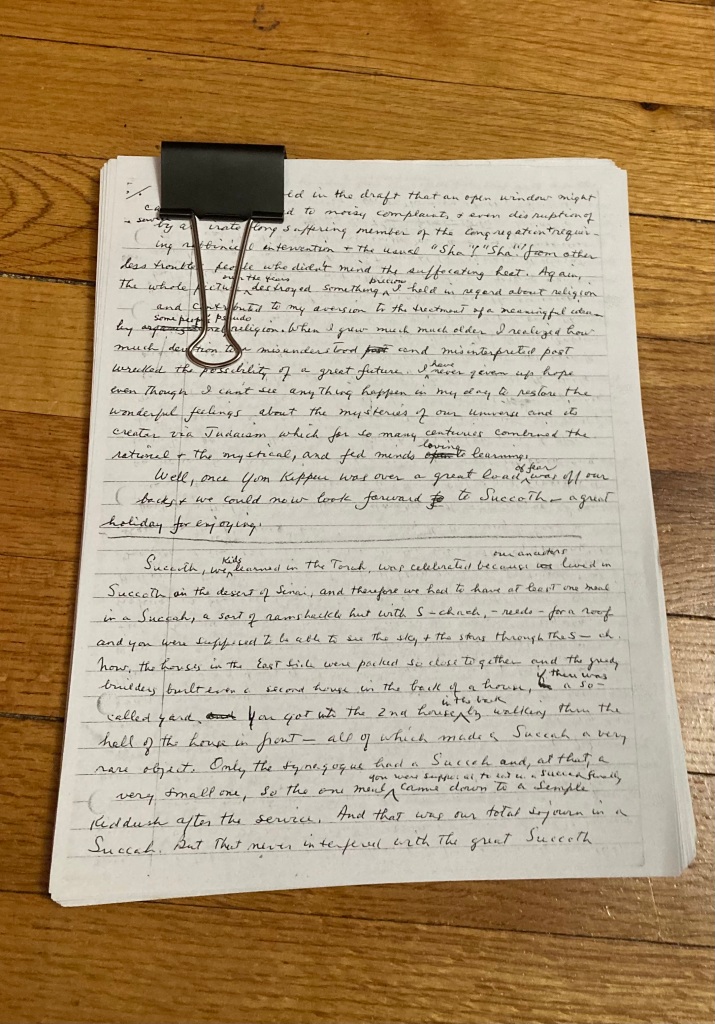

Recently, I realized that while I had typed up all of my grandfather’s letters back and forth with his father (despite many of my great grandfather’s responses being in Yiddish and broken English) and my grandmother’s travel diaries (listing all of the things she hated about each country she visited) and all of the children’s stories my grandfather had written for his grandchildren, or at least the ones that I could find, I hadn’t typed up his forty some odd page memoir, even though I was sure I had. We’ve had copies of his handwritten memoir forever, and maybe that’s why I assumed it had been typed up or at least scanned into the computer at some point, but no.

So, since I’m on summer break from work, I decided to type the memoir and give myself the opportunity to hear my grandfather’s voice once again.

I had four grandparents, of course, but my father’s parents were both difficult people with not-so-great English who were unlikely to write down their thoughts in any language. And my mother’s mother, who wrote quite a lot, was not the most generous soul, so reading through her poems and essays, can be, at the very least, claustrophobic.

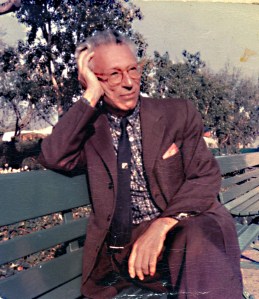

But my mother’s father was a writer (as well as a teacher) and towards the end of his life he decided to sit down and write an account of his childhood, specifically for his grandchildren. He wrote, early in the pages, that he wished he’d had such an account from his own grandparents, and so he wanted to make sure to do that for us.

For the past few weeks, whenever I’ve had time, and energy, I’ve been sitting in front of the computer transcribing a few pages of my grandfather’s handwriting – hearing his unique voice and how he played with punctuation (a dash here, a comma there, often both at the same time) and how he often repeated words for emphasis, like hard hard, for very hard, or much much, for very much. Interestingly, I’ve noticed this same pattern in Modern Hebrew, where le’at le’at (or slow slow) means very slowly, and maher maher (or fast fast) means very quickly.

I was sure I remembered everything important from having read the memoir years ago, but of course there were so many things I’d forgotten: like his descriptions of the outhouse behind the tenement across the street, and how lucky his family was to live in a tenement that had two indoor toilets per floor; or his description of all of the wonderful food his mother made for holidays, or the deep anxiety she lived with year round and that was finally echoed by everyone else during the High Holidays; and there were all of the stores he accompanied his mother to, when he was only four years old, because his English was better than hers; and the way he described his childhood synagogue on Yom Kippur, where the Cantor would close the windows, to avoid catching a cold from the breeze, leaving many people struggling with the heat, and fainting from the combination of the heat and the hunger from fasting.

My grandfather was a wonderful storyteller; I’ve always known that. And he had strong feelings about the ways his childhood orthodoxy no longer fit him as he grew up and began thinking through his Judaism for himself. And I knew that he loved language and food and his family. None of the information or the wisdom in these pages is new to me, but I am so grateful for the opportunity to dawdle over these pages again and to take my time as I type (because I am a very slow typist) and visit with him again.

In the midst of the typing, my great aunt Ellen, my grandfather’s baby sister, died at the age of one hundred and eight. She had outlived the rest of her siblings by decades, taking on the mantle of family elder and family glue. And with her death it feels like a whole generation is disappearing at once, except for all of the memories they’ve left behind, including this memoir my grandfather wrote just a few years before he died. These forty short pages are giving me a chance to have conversations with him that we never got to have when he was alive, and I am so grateful to have these words to help keep his memory alive, and the memory of his baby sister whom we loved very much, and, who, as a result, we will never really lose.

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my Young Adult novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?