I never learned how to play chess. My father tried to teach me at some point, but for a man who made his living as a teacher, he was crap at teaching me: he was impatient, he blew up, he forgot to how to teach and just gave me the instructions you might find on the back of a cereal box. When my older nephews started to play chess, to the point of taking lessons and competing, I still didn’t get involved. I would play a game of make believe with them or go on any nature walk they wanted, but I could not and would not play chess.

But recently, after adding yet another language to my Duolingo list (Arabic), and struggling to figure out the alphabet and how the letters change when they are at the beginning, middle or end of a word, I got a notification that Duolingo now teaches chess, and just as an escape, I decided to try it.

In general, I like the way Duolingo approaches teaching. I like that it’s fun and the lessons are short and that you learn by doing rather than by reading, but they often go too fast for me, jumping through the early stages of a language or skill, and leaving out necessary steps or repetitions. Given all of that, I enjoyed the first few chess lessons, where they showed me what each piece on the chessboard is allowed to do and gave me a chance to practice, but too quickly, they moved on to lessons on strategy (move your knight here to block a potential attack, convince your bishop to die to save his queen, if all else fails run away). Of course, I made a million mistakes, and since I only have the free version of Duolingo, I had to watch a million ads to earn enough lives to redo the lessons, over and over, until they started to make even a little bit of sense.

As with Arabic, and Yiddish and German and Spanish before it, I resent that Duolingo gives me so few points for reviewing lessons, and so many for constantly moving forward. It mimics real life, where speed of progress seems to be more important than knowledge retention, or mastery, or sanity, and just like in real life, it leaves me feeling like a failure.

I was always a smart kid, so people assumed that I could pick up any new material easily, and sometimes I could, but when I needed more time or explanation to figure something out, teachers got impatient with me. I remember loving my math workbooks as a kid, because for each lesson there were pages of exercises, and I could practice until I not only understood what I was being taught but could do it automatically. Ideally, I would have had a stack of workbooks for every skill I’ve needed to learn, like how to open a bank account, or pay bills, or buy a car. Why is it assumed that people will just know how to do all of these things on their own? Even with Professor Google around to give us endless information, we still need support and advice and time to master new skills. Don’t we?

Anyway, the shame I keep feeling at the things I don’t know how to do, and don’t know how to learn how to do, keeps getting in my way, and what I seem to need, whenever a skill seems too complicated or overwhelming, is to be able to break it down into bite-sized lessons and practice all of them until I feel confident enough to move on to the next. So, I’ve been practicing how to give myself that time and compassion with chess: repeating the same lessons over and over again, for very few points, until I feel secure enough to move forward, no matter how little reward Duolingo chooses to give me for my efforts. And, no, I don’t think that learning how to play chess will fix my brain, or my life, but maybe building these habits while learning how to do this thing that in every other way is meaningless to me, might help me figure out how to learn the things that really matter to me, helping me map out the steps I need to take, rather than the steps that other people assume should be enough.

The problem is that, in Duolingo as in life, I keep forgetting my overall goal in favor of wanting to win at the current game. I crave the validation that comes with earning points and rewards, or praise and acceptance, and I forget that that’s not the goal I was shooting for in the first place. It’s kind of like how I can start the day planning to eat the right balance of protein, fat, and carbs and then I’ll see a box of cookies and completely lose my way. But that’s what practice is for, right? So that even if I go off on a cookie tangent every once in a while, I’ll remember how to get back on track. Though, right now, all I can see in my mind is a road paved with chocolate chip cookies, coated in milk chocolate, and colored sprinkles.

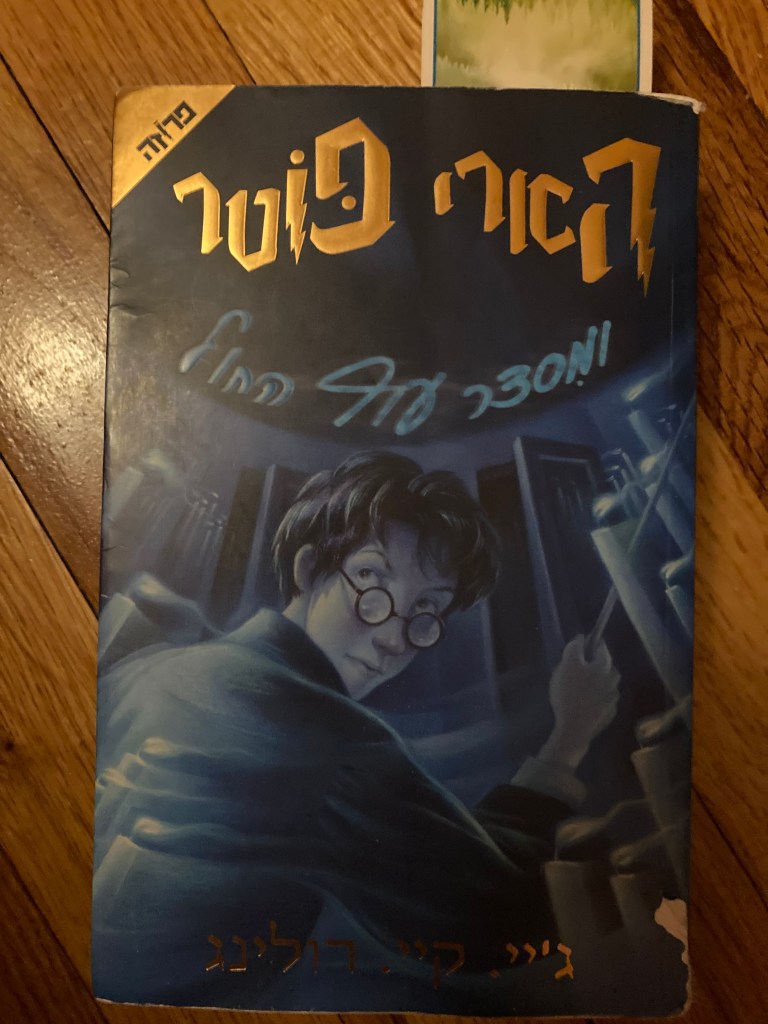

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?