A few weeks ago, Mom was struggling. Her blood pressure kept dropping too low, even when she forced herself to drink the liquids the nurse at the cardiologist’s office had recommended; and instead of needing one nap, or two, she could barely get out of bed. And then, even a sip of coffee was too much to swallow. But she didn’t want to wake me up to tell me she was in trouble, so she waited until I woke up on my own, looked in on her, and freaked out.

We arrived at the Emergency Room around Noon and there was a line to check in, so after making sure she had a place to sit and nurses nearby, I went back to park the car – which I’d left running, with the doors open, because I wasn’t panicking at all. By the time I got back, she was doing her intake interview, and another member of the staff took me aside to sign a few papers – including one that said I promised not to be physically or verbally abusive to the hospital staff (it’s kind of scary that such a document needs to exist, but I watched season one of The Pitt, so I get it). Then they gave Mom a gown, did an EKG, and led her to a stretcher in the hallway, because all of the actual rooms were full; most of the stretcher spots were filled as well, even though it was the middle of the day, in the middle of the week, in the middle of winter.

I stood aside while a nurse took blood and a tech did a portable chest x-ray, and in the meantime, a woman nearby (who was there with her own mother) told me how amazing Mom is, because while they were waiting in line to check in, Mom calmly told the intake nurse that she was having a heart attack. I turned to stare at my mother and she looked sheepish. She hadn’t said a word to me about a heart attack.

Luckily, the EKG and chest x-ray and blood tests all came back clear for any signs of cardiac distress. What they did find, though, was low hemoglobin levels, A.K.A. Anemia. And the doctor seemed to think that all of her symptoms could be explained by that diagnosis: the low blood pressure, the exhaustion, the nausea, even the tightness in her chest and shortness of breath. Her hypothesis was that the Anemia was caused by internal bleeding, because of an ulcer, because of the Ibuprofen Mom’s been taking for pain in her leg and feet, but they would need to do more blood tests and a CT scan, and have her checked out by a cardiologist, just in case.

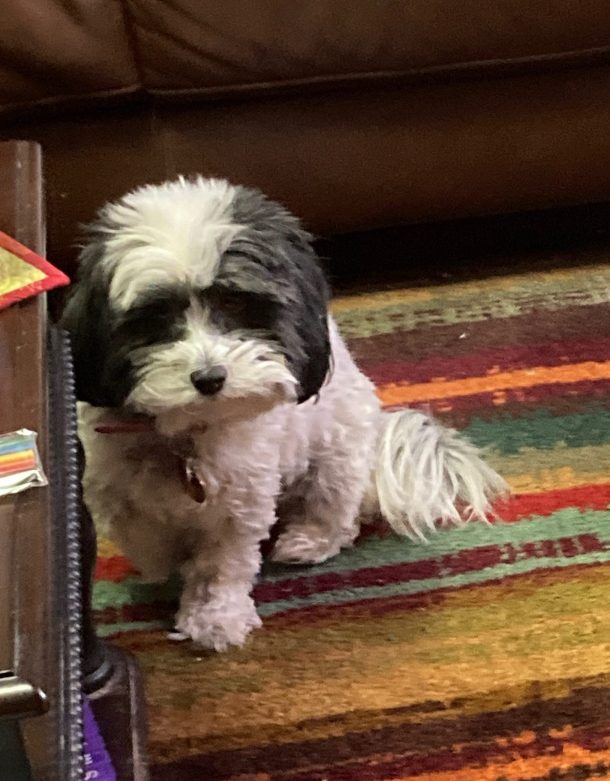

Mom kicked me out of the ER just before dark, because I hadn’t eaten or taken my meds before driving her there in the first place, and because I was distracting her from her phone. My hope was that I would be able to rest for a few hours, and then she’d call me to pick her up before bedtime. I stopped at the supermarket to stock up, making sure we had enough coconut water and grape juice to keep Mom’s fluids high, and when I got back to the apartment I found out that Tzippy had thrown up on the floor, right next to Mom’s side of the couch.

I put the groceries away, cleaned up the floor, and the wee wee pads, and Tzippy’s bed, and then we sat together in the living room, watching TV and waiting for news about Mom. I spoke to my brother, and my aunt, updating them on the situation, and texted constantly with Mom to keep up with the latest events at the hospital. By 8 or 9 o’clock, the nurses told her that she’d have to stay overnight so they could do an endoscopy in the morning, and I finally changed into my pajamas and gave Tzippy her last treat of the day, but neither of us got much sleep that night.

The endoscopy didn’t end up taking place until early afternoon the next day, and then they found Mom a hospital room and told her she’d be staying for a few days. I packed her a bag (she wanted her weaving supplies, and I had to remind her that she might also need some clothes), and drove back to the hospital, carrying her loom through the metal detector. She was clear eyed, if exhausted, and relieved that she’d finally been allowed to eat, now that the endoscopy was over. The nurses were wonderful, as usual, but they’d had to poke her multiple times before getting the IV in the right spot, so her arms were black and blue. Thankfully, now that the IV was in a good place, they could administer medications without re-poking her, and the stomach protectant and IV Tylenol seemed to be helping.

But there were still more tests to do, and more doctors to see, and Mom and I were both anxious and confused about what was going to happen next. My brother was able to speak to the doctor over the phone and then visit in person to explain some of the things the doctors were leaving out. They ended up giving her a transfusion, because her hemoglobin levels were still low, and more fluids, and then they did more tests and checks and, finally, on day five, they let me take her home.

She already looked better than she had in months, so the Anemia must have been going on for quite a while before it became acute, but Mom was just happy to be home again, to see Tzipporah, and me, but even more so to be free to leave her bed without an alarm going off each time her foot touched the floor. She even committed to her new bland diet, to manage the ulcer, and was inspired to find a similar diet for Tzipporah, to see if that would help her too, and to have a diet buddy, of course.

Each day since then, Mom has been looking a little bit better and more like herself, though she still thinks she’s resting too much and getting too little done. And Tzippy seems to be feeling better too. They’ve both happily returned to their regular routine of arguing at bedtime: when Tzippy gets three treats and demands a fourth, and Mom tries to hold her ground, and then sprinkles cheese on the kibble, and Tzippy cries because what she really wanted was another chicken treat and why doesn’t her grandma understand?

As I listen to their duet from my room, I am relieved to be surrounded by family noise again. While Mom was in the hospital, I was in a state of suspended animation, checking my phone constantly and feeling like my whole world depended on the next piece of information. And it’s such a relief not to be so anxious anymore, though I’m much more aware now of which doctors Mom needs to see, and how much liquid she’s consuming and which foods she’s not supposed to eat. I’m also much more aware of how annoying it is to have to shovel the car out every time you need to go to a doctor or hospital or pharmacy (or work), when all you really want to do is hibernate under the covers and never see a snowflake again.

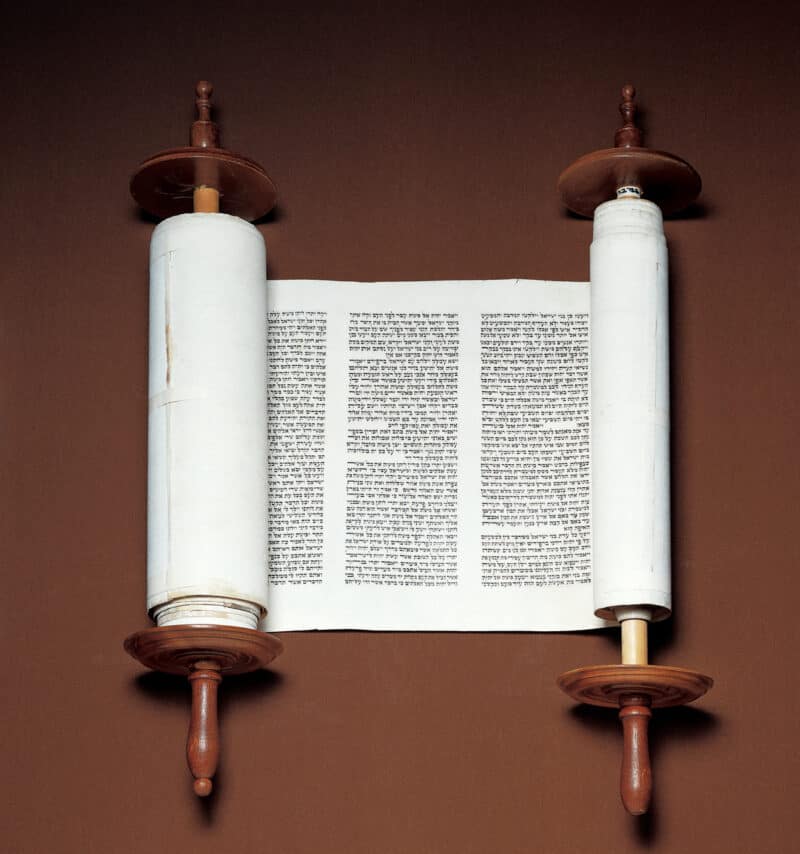

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?