I’ve been watching videos in Hebrew for a while now, to practice my listening skills and to get a wider sense of Israeli culture, and one of the richest sources for short (2-15 minute) videos is Kan Digital, the online section of the public broadcasting channel in Israel. I have no idea how many of these videos actually end up on TV in Israel, but there are tons of them available on YouTube; along with a really great interview series by Orit Navon that delves into serious subjects (mental illness, living with disability, bullying, grief, having one Jewish and one Muslim parent), there are also videos by a variety of reporters/performers from different segments of Israeli society (religious and secular, Ethiopian and Russian, Israeli Arab, Jewish, Muslim, Christian, etc.), on a wide range of subjects, from serious, fact-based pieces on how Israeli elections work, to slice of life videos about working from home during Covid, to a dance video on how to choose a watermelon.

Recently, I saw a video from one of the usually less serious performers/reporters (he did the watermelon video), where he’s sitting in what looks like a real therapy session, or a very close facsimile thereof, and both the reporter (Ehud Azriel Meir) and the therapist seem to be from the Religious Zionist community (roughly equivalent to Modern Orthodox in America – which you can tell from their crocheted kippot and casual clothes, as opposed to the more formal clothing and black hats worn by Haredim/ultra-orthodox). I’d seen a lot of videos from Ehud before; he did a whole series where he was supposedly sent to work with the Arabic language division at Kan to create educational videos about Jewish holidays and rituals, and each video in the series poked fun at all of the assumptions Jews and Muslims and Christians in Israel make about each other. It was silly and light, but also allowed for a pretty deep exploration of social conflicts Israelis grapple with on a daily basis. In general, Ehud’s videos are like this, characterized by humor and a willingness to show his own flaws and mistakes, but the video with the therapist had a much more serious tone than I was used to from him.

The therapy session starts with Ehud’s feelings of guilt at wanting to vote for someone other than the Religious Zionist candidate in the coming election. He believes that if he votes for “the other” candidate, he’s not only letting his own side down, he’s letting the other side win (though in Israel’s multi-party system there are always more than two options). This led to a discussion of the moment he started to feel some alienation from his own political party, which is also his religious community, way back in the 1990’s, when Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin was assassinated. Before the assassination, Ehud, as a teenager, took part in a lot of the demonstrations against Rabin’s push for the Oslo Accords. He and his fellow Religious Zionists believed strongly that the accords would lead to more terrorism rather than to peace, and they were loud and vehement in their opinions, calling Rabin a traitor and a murderer. And then, Yigal Amir, also a Religious Zionist, shot and killed Rabin at a peace rally.

For Ehud, Rabin’s murder was a moment of awakening. It truly devastated him that this man, who was like a father to him and to the country as a whole, had been killed by someone on “his side.” He had never considered the possibility that people were taking those screamed epithets literally, but when he and his friends tried to go to the vigils to mourn Rabin with the rest of Israel, they were turned away. And, still today, he resented that the secular Israelis blamed him for Rabin’s death, and he felt like it would be disloyal to his own group, and to himself, to vote with them on anything, even when he agreed with their policies.

The therapist pushed Ehud to acknowledge that his strong feelings around all of this might mean that he did feel somewhat responsible for Rabin’s murder, and that maybe he was uncomfortable in both the Religious and the secular worlds because he was still trying to avoid facing those feelings of guilt. Ehud bristled at that idea, but the therapist persisted, suggesting that in order for him to be at peace with having one foot in each camp, he needed to wrestle with the ways he himself believed that his actions long ago may have done harm, and to acknowledge that no matter how much he treasured his identity as a Religious Zionist, that wasn’t all of who he was.

There was something really powerful for me in watching this usually very un-serious guy, now grumbling and uncomfortable, being willing to share his discomfort and uncertainty with the public, in case it might do some good. And his internal conflict resonated with me too, even more so because he used the words Gam ve Gam (Both/And) to describe his feeling of being both a Religious Zionist, and something else as well.

Whenever I start a new semester of online Hebrew classes, I’m asked if I prefer my name to be pronounced the English way or the Hebrew way, and I always say Gam ve Gam, both because I grew up going to Jewish day schools where half the day I was one and half the day I was the other, but also because the feeling of having different parts of me that fit in with different groups is a big part of my everyday life. It can be really hard to live in the Both/And. I’m never sure if I should stand with one foot in each camp, or hop from one side to the other, or stand in the middle all by myself. More often than not, I feel like I have to hide parts of myself, or act in ways that feel wrong to me in order to fit in.

Watching this video reminded me of the traditional Ashamnu prayer that we say during the Jewish high holidays each year, where we pound our chests and admit to all of the possible sins that may have been done by a member of our community. That level of exaggerated responsibility has always bothered me, because I work so hard to make sure I do no harm, and it doesn’t seem fair that I should have to take responsibility for Joe Schmo over there who couldn’t care less who he hurts. It’s not even clear which community the prayer is referring to: does it include all Jews? All Jews on Long Island? All human beings on earth?

But now I wonder if the prayer is trying to get at the collective guilt we tend to feel when someone from our own political party, or tribe, or family, does something wrong. Even if we are not directly responsible for an evil act, we may have played a role in creating the conditions for that evil act to take place; or maybe our strongly held beliefs led us to encourage someone in the direction that led them astray; or maybe we were silent when we knew we should speak up, because we were afraid of being kicked out of the group; or maybe we felt responsible simply because outsiders told us that we were responsible, because they see our group as a single entity rather than a collection of individuals.

Once a year, this prayer gives us the opportunity to acknowledge those complex feelings of communal guilt, and reminds us that we need to recognize the impact we can have on the people around us, whether we intend that impact or not. And maybe most of all, the prayer reminds us that even when we disagree with our fellow community members, and speak up against them, we are still part of that community and that community is still a part of us.

I had a Creative Non-fiction teacher back in graduate school who told us that in order to write a good essay (for her class, at least), we needed to write about two seemingly unrelated subjects at once. For example, if you’re writing about pizza, you could also write about existential philosophy; or if you are writing about fashion, you could also look back at a memory from a childhood dance class, or a nature walk, or a chess game. Because, she said, the most interesting material comes from the way those two unrelated topics brush up against each other and create something new. And I think that’s true of more than just a good essay. When I live my life in both A and B (and often in C and D and E as well), the friction that comes from those mashups creates a lot of sparks, and what would our lives be like without all of those sparks to help light the way forward?

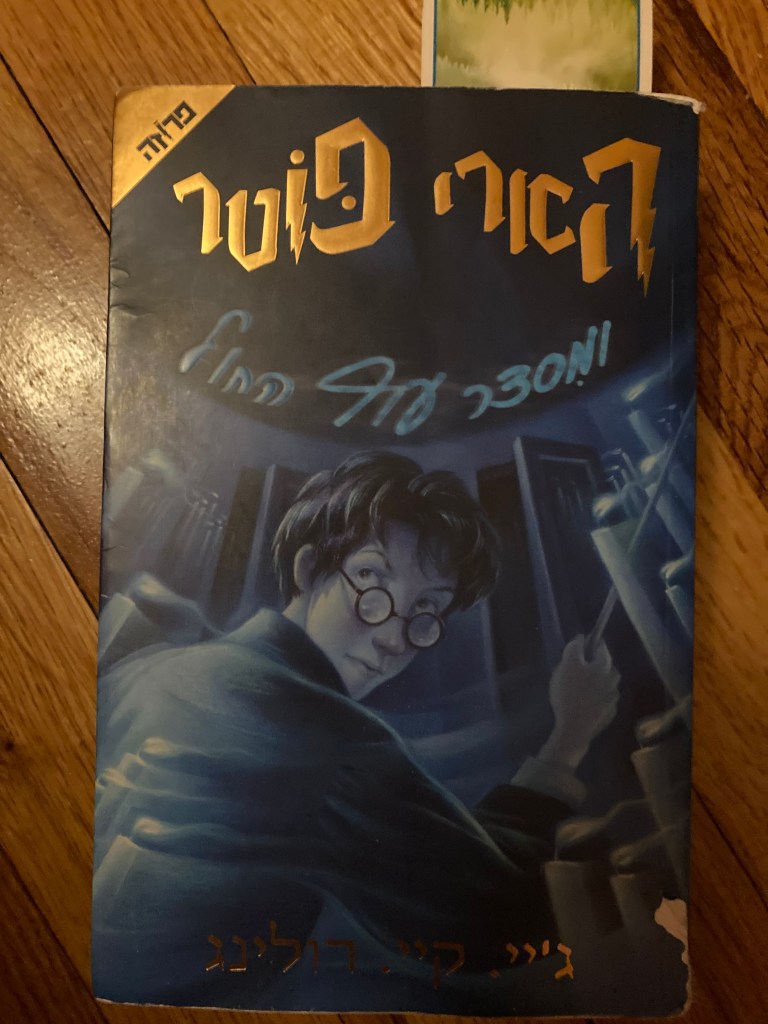

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?