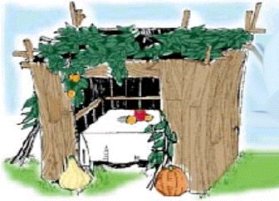

After Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur – the big Jewish holidays where even unaffiliated Jews go to synagogue, or fast for a day, or at least eat brisket in a nod to tradition – comes Sukkot, the holiday where Jews build huts in their yards and eat under the stars for a week. This used to be the biggest Jewish holiday of the year, back in ancient Israel. It was a celebration of the harvest, with everyone traipsing to Jerusalem to see and be seen. Today, among liberal Jews in America, Sukkot doesn’t get much attention, coming as it does four days after Yom Kippur, when everyone is sick of being Jewish, or at least of going to synagogue. And that’s unfortunate, because Sukkot is meant to be a happy holiday, with Sukkah Hops (visiting everyone else’s sukkot/huts to eat cake and cookies and just hang out and gossip), and waving palm fronds, and sniffing citrons (etrogim), and all kinds of weird traditions that keep things interesting and happily silly.

But a year after the October 7th Hamas attack on Israel, which took place during the later days of the holiday of Sukkot, celebrations of the holiday are more complicated. It’s hard to celebrate when Israel is at war (with Hamas, Hezbollah, the Houthis, and, ultimately, of course, with Iran), 101 hostages are still being held in Gaza, and antisemitism is rising around the world. But celebrating Sukkot is an obligation, and one of the other names for this holiday is Zman Simchateinu (the time of our happiness), so we are obligated not only to go through the motions of erecting a sukkah and saying the blessings over the Lulav and Etrog, but to find moments of true joy as well.

At my synagogue, we build a sukkah each year (well, someone builds it), and we try to have as many services and events and classes as possible in the sukkah, in order to give everyone a taste of the holiday, since most of us aren’t building our own sukkot at home. And at the synagogue school, we try to make a big deal out of the sukkah in the courtyard, and to engage the students in seeing the holiday through different perspectives. This year’s theme is looking at the connection between the sukkah we build for the holiday of Sukkot, and the more figurative Sukkat Shalom, or Canopy of Peace, that we sing about each week in the Hashkivenu prayer at Friday night services. The most obvious connection is the word “sukkah,” which can be translated to mean booth or hut, as it is for the holiday of Sukkot, or canopy, as it is in the Hashkivenu prayer, where we ask God to cover us with a canopy of peace; but even more so this year, we are looking for a connection, or hoping for a connection, between these days of Sukkot and peace.

In Leviticus 23:41-43, we are told that living in a sukkah for a week each year is a reminder of the Exodus from Egypt, and the forty years our ancestors spent in the desert afterwards before entering the promised land. But, given that we remember the splitting of the Sea of Reeds in our daily prayers, and spend the whole week of Passover remembering the Exodus from Egypt, the fact that Sukkot is also a time for remembering the Exodus is often forgotten, in favor of the lulav and the etrog and the sukkah and all of the food. But this is a Jewish holiday, and there is no such thing as a simple Jewish holiday; even at a Jewish wedding we manage to remind ourselves of tragedy (stepping on the glass to remember the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem, and/or to scare away evil spirits). So, it’s not surprising that even during this holiday of happiness, even during a year when we’re not in mourning, we are still called to reexperience suffering.

The sukkah, which really looks ridiculous if you think about it, with its open door and barely covered roof, is a representation of the fragility of life and our imperfect safety in the world, and in both of those ways it is meant to remind us of our dependance on God. And yet, we are commanded to enjoy life in this sukkah, and invite friends and strangers inside to eat with us. We are called to practice creating joy even in the midst of difficulty, because that’s a time when it feels unnatural but is essential to remember that joy is possible.

And I think that may also be the lesson with our Sukkat Shalom, our figurative canopy of peace: that even with God’s protection our lives will be imperfect, and our experience of peace will be imperfect, and temporary.

And that sucks. I have always wanted to believe in a future filled with an idyllic peace – a world full of comfort and kindness and all of our needs being met – despite never actually experiencing such a thing; even the hope of such peace in the future has been enough to keep me going. But what if this imperfect peace, filled with moments of suffering and fear and open doors and leaky roofs, is the only kind of peace that’s really possible? What if our prayers for peace have already been answered, but because we were looking for something more perfect we can’t recognize it?

We tend to think of peace as an absolute: we are either at peace or at war. But what if peace is complicated, or exists along a spectrum? American Jews are facing a dramatic rise in antisemitism, and grief and confusion and anger over what’s happening in Israel, but even before October 7th peace in Israel and for American Jews was never perfect (Israel was in the middle of yet another ceasefire with Hamas when the attack occurred, after all, and the past few years in America have not been free of antisemitic acts by any means). There is no time in history free of all difficulty. And maybe these holidays, which we are obliged to celebrate every year no matter what circumstances we are living through, are not about keeping us on our guard, or depressed about our lack of safety, but to teach us that even in an imperfect world we can, and must, live our lives as joyfully as possible, as fully as possible.

It’s a hard lesson to learn, and even harder to teach, honestly. But Sukkot gives us a yearly opportunity to practice living in and appreciating an imperfect peace. We can sit in our fragile shelter and feel the chill in the air and watch our napkins fly off the table, and still eat good food and laugh with our friends and sing together, feeling gratitude for what we have, and grief for what we don’t have, at the same time.

Feeling multiple things at once isn’t the only lesson of Sukkot, but it might be the most useful one for this particular moment in Jewish history. And, it may actually be the key to all of the other life lessons we want our students to learn. We often think of resilience and mental health as the ability to focus only on the positive, but in reality, resilience is the ability to accept life as it is, and continue on. Like it says in Ecclesiastes, there’s a time for everything, a time to plant and time to uproot, a time to mourn and a time to dance, a time for peace and a time for war. We are meant to live in all of it, eyes open, taking it in and seeing it for what it is. And even, or most importantly, saying a blessing over what we see.

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?