The Cantor at my synagogue has taken up a new topic to study this year: the technology of prayer. I can’t say that I understand what he means by that yet, but the first lesson was about sacred space, and how we arrange it. Butterfly is very often in sacred space, because she listens to the sounds around her and stands still and lets them encompass her. Cricket prefers hidey-holes as her sacred spaces. She feels safe and solemn in those small, enclosed spaces, and it allows her to rest and reemerge more whole.

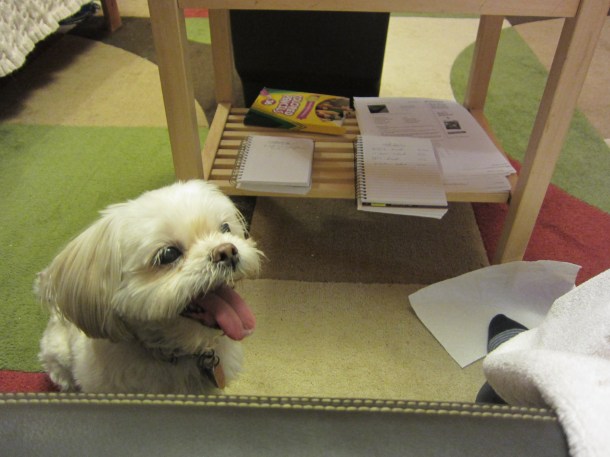

“You can’t see me!”

“I hear everything, Mommy.”

But, I am not good at interior design. When I decorate, I basically put things where they’ll fit, no Feng Shui or harmony involved, so the idea of contemplating the use of space made me whimper with anticipated boredom. The cantor talked about how most sanctuaries, Jewish and Christian at least, are set up with the congregation in rows of seats, all facing one way, with the clergy up on a riser, and the congregation a step down, like an audience watching actors on a stage. Then he showed us pictures of Jewish synagogues that were set up differently, with the congregation on two opposing sides, or even three sides of the sanctuary, and the clergy in the middle. The idea being to focus attention on the community, rather than on the clergy, who are there to lead the congregation, rather than to be the show itself.

The Cantor’s class on sacred space happened the night before Slichot, which is a service that takes place a week before the Jewish New Year, late at night. It is a preview of all of the themes of the high holidays, with all of the atonement, forgiveness, and cleaning of old forgotten laundry intended for this time of year. But for this one service of the year, the clergy members placed themselves with us in the congregation, and some of the ideas from the previous night’s class must have stuck with me, because as soon as the Cantor began to sing from his seat among us, I felt the change in the shape of the space. I got it. He became one of us instead of separate, and he became a voice only, rather than a performer to be watched. It was a small group the night of Slichot (not a lot of people come out a week before the high holidays, at ten o’clock on a Saturday night, to pray), which meant that the Cantor didn’t need a microphone to be heard, so that his unamplified voice, so intertwined with our own, made him seem even more a part of us.

Over the summers, at our synagogue, we move from the formal sanctuary to the small sanctuary for Friday night services. It saves on electricity, especially for the air-conditioning of the sanctuary and the social hall, and it saves us from seeing all of the empty seats from the families who go away on vacation, or just don’t feel especially religious in the heat. But the side effect of moving to the smaller, less formal room, is that our whole tone changes. The clergy stands at our level, and not above. We sit closer together, instead of spread out across the room. We can hear each other sing, and breathe. The space itself, usually just an ordinary room, becomes sacred space because of how we live within it.

Maybe sacred space actually changes from person to person and moment to moment. A lot of the time, I think a space feels sacred because of the people who are in it with you. That’s why I wish that the dogs could join me at synagogue, especially when we are at our most informal and communal. Cricket could sit in my lap, or hide under my chair, and Butterfly could wander around the room and listen to all of the voices around her. That would be my ideal of a sacred space.

That’s Cricket’s foot.

Cricket in her sacred space.

Butterfly’s not allowed in, but she makes do.