Shpilkes is a Yiddish word that literally means “pins,” but has come to refer to “sitting on pins and needles,” or, feeling fidgety and nervous and needing to move.

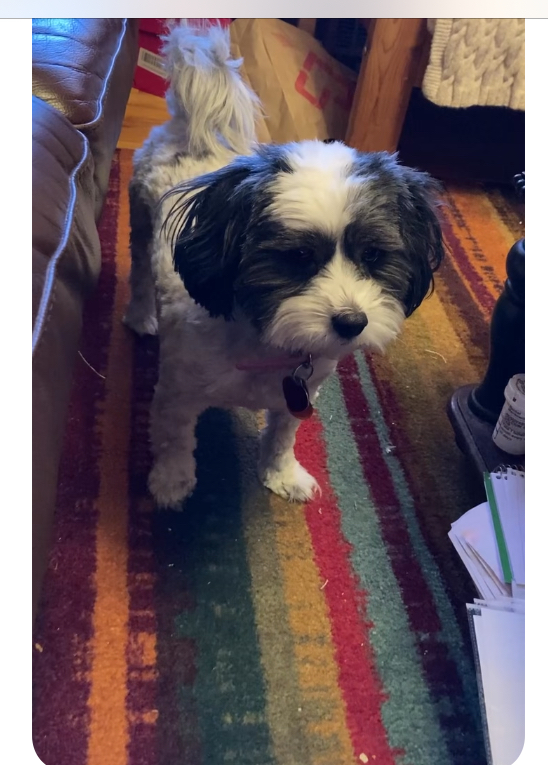

When I teach this word to my students, I tend to liken it to the ADHD symptoms they see in so many of their classmates (because even the undiagnosed kids seem to have shpilkes by the end of a long school day, which is when they come to me). This time, I was sitting with a mixed age group of kids, from second to sixth grade, for our twenty-minute elective period at the end of synagogue school for the day, and we were all exhausted and ready to go home.

I gave them the option of sitting at their desks or on the floor, but most of them chose to sit at their desks, except for the one girl who chose to sit in my rolling chair, so I sat on the floor by myself. Whatever. As a warm up, I asked them to repeat the word “shpilkes” with me, over and over, because it’s just fun to say. We’d already done a session on Kvetching (complaining) before the holiday break, and I knew we weren’t ready to move straight to Kvelling (expressing joy at someone else’s accomplishments), so shpilkes was the next step on our Yiddish ladder.

Once they’d giggled through the word a few times, I asked them if they had ever experienced having shpilkes themselves, or if they knew someone else who struggled to sit still, and they told stories about friends who couldn’t sit still, or couldn’t shut up, though no one was willing to jump in yet and admit that they themselves might struggle with sitting still. Then, one girl raised her hand shyly and said, I know someone who’s the opposite. She can get so focused on reading a book that she doesn’t hear what’s going on around her.

I asked if anyone else knew someone who could get so caught up, or if they’d experienced something like that themselves, and the stories kept coming. And then one of them asked, do you know the feeling when a song gets stuck in your head and you can’t get it out! Which led to an in-depth discussion of earworms and what causes them and how to treat them. One girl had developed a whole theory, saying that earworms are caused when you forget some of the lyrics to a song you like, so your brain just keeps repeating the song to try and remember the lost words. Her suggested treatment was to go to Spotify and listen to the song until the earworm crawled away in defeat, which, she said, worked every time.

Aren’t our brains fascinating?! I said, from my seat on the floor. By then, one of the students had joined me on the floor, because all this talk of shpilkes had reminded him that chairs and desks are confining and it’s much more comfortable to stretch out.

But, what about when one friend has shpilkes and the other friend has to deal with the consequences? Because, my friend keeps getting us into trouble when she talks in class, and she can’t help it, but we’re going to get kicked out and I really like that class.

To which one of the younger boys said, Yeah, it’s hard when you can’t understand why someone acts the way they do, even though you still like them and want to spend time with them. I’m paraphrasing, but only a little.

And with minutes left to go, and so many more stories to tell and hands raised and legs swinging, I asked them if they’d ever seen a show called Glee (a few of them had, actually. Streaming makes everything new again). Glee was a TV show about a high school glee club, where they often took two songs from different genres and mashed them toegther, and sometimes, not all the time, the mash-up allowed us to hear each song in a new way because of how the two songs spoke to each other. The kids didn’t even need me to hammer the point home. They already had their hands up with stories to share about their friends who are really different from them but make life so interesting.

Of course, my most literal student asked if I could supply examples, and I did try to find something from Glee on my phone, but the dismissal announcement interrupted me, and then we had to focus on listening to the walkie talkie calling out names one by one. But even then, more stories were spilling out, and each story reminded someone of another story, and another.

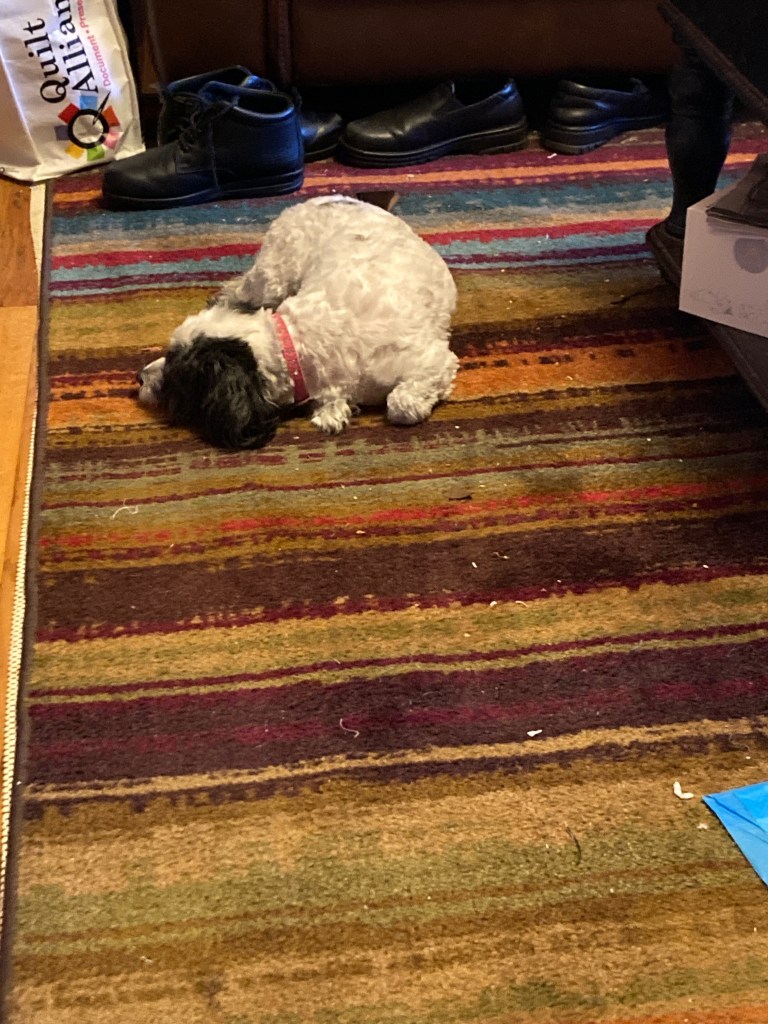

It doesn’t always go like this. My current regular class has so much collective shpilkes that it feels like we’re hiking through a tornado just to get from the beginning of a sentence to the end. But sitting on the floor, listening to the stories flow around the room, reminded me that they all have so much going on inside of them, and sometimes, if I’m very lucky, they will share their stories with me in a way I can hear them.

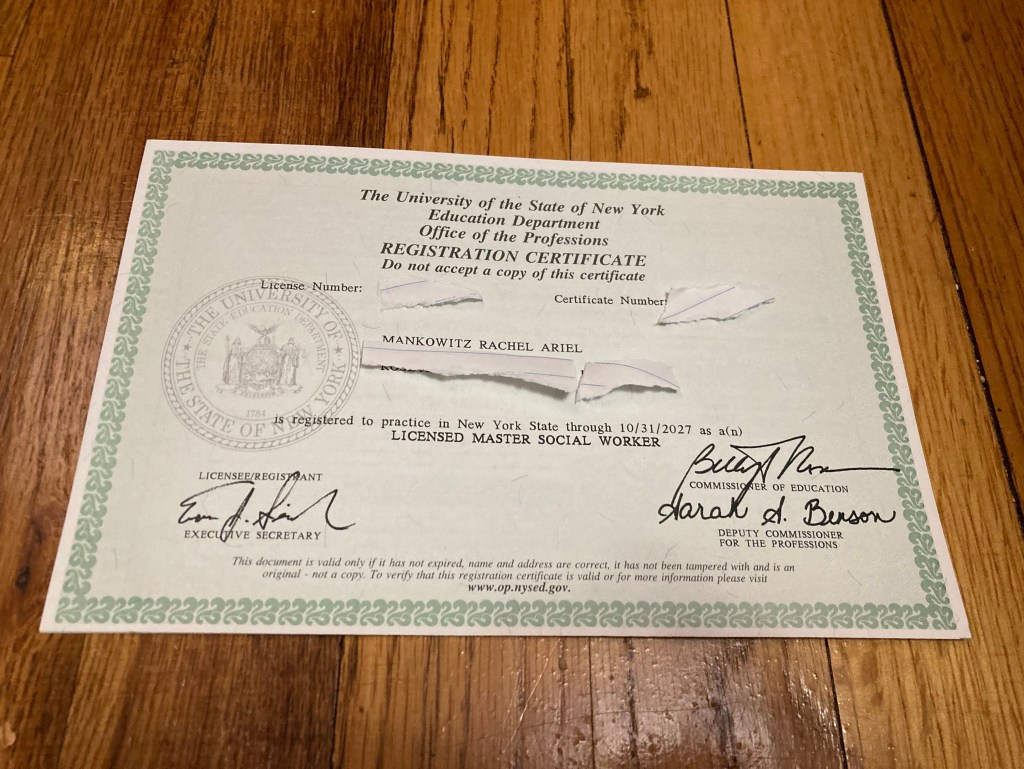

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?