Over the Jewish high holidays I noticed all over again how many women in my congregation wear a tallit, a Jewish prayer shawl. I grew up at a time when it was rare for women to wear a tallit, and rare for women to become rabbis and cantors, though there were some. At summer camp there were one or two women who wore a tallit (and a kippah and tefillin), but they were outliers. I had my Bat Mitzvah at thirteen and led the service and read from the Torah, but I wore a nice dress, blue I think, and no tallit.

A tallit, or Tallit Gadol, is worn over the shoulders at morning prayer services (and one evening service per year, on the eve of Yom Kippur), as opposed to the tallit kattan, worn by boys and men under their clothes. There are fringes at the four corners of the tallit, called tzitzit, each made of eight or so strings held together with four knots, with one blue thread. Most synagogues have extra tallitot (the plural of tallit) and kippot (the plural of kippah, or skullcap), outside the sanctuary for those who don’t have their own.

In Rabbinic Judaism, women are not obligated to wear a tallit, but Orthodox Judaism actually forbids women from wearing them, and growing up, this prohibition was front and center for me at my orthodox Jewish day school. The rabbis told us that men needed these reminders more than women did, and anyway, women would be too busy taking care of the children to get to synagogue for services on a regular basis. They explained the prohibition against women wearing tallitot as part of the prohibition against women wearing men’s clothes, which they took seriously in our school, where girls were forbidden from wearing pants. Despite my frustration with their patronizing logic, I still never thought of taking on the obligation of wearing a tallit myself.

The female rabbi at my synagogue today, though, wears a tallit, and many women in our congregation wear not only a tallit but also a kippah, traditionally the men’s head covering. We’ve had generations of Bat Mitzvah girls and adult Bat Mitzvah groups at our congregation now, so that women of all ages have gone through the process of choosing their own tallitot to fit their personalities and feel welcomed as equal members of the Jewish people. I like so many of the women’s tallitot that I’ve seen, in pinks and reds and purples, with beautiful designs and embroidery, and I love the idea that women are seen as just as important as men to the maintenance of the community. I even have my grandfather’s tallit in a cabinet, because it matters to me, but I’ve never worn it, and I’m not sure why.

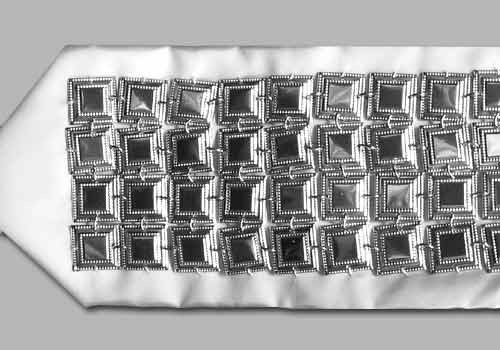

Maybe it’s just habit, after years of not wearing one; or maybe it’s because of the obligations and commitment it represents, and I’m not ready to take that on; or maybe it’s my father. I loved my father’s tallit. It was the size of a beach towel, with thick black stripes and sterling silver squares covering the atarah, or yoke, of the tallit. It was like a huge tent that could be folded over at the shoulders to give him wings, or spread over his head so he could disappear underneath it into his own personal relationship with God. I think that any tallit I might try to wear, no matter how feminine, or light, would feel like draping the power of my father over my head, and I know in my bones that instead of making me feel safe, it would suffocate me.

There are so many things like this, still, in my life, so many relics of the past that I have tried to re-value and scrub clean of their old associations. I have overcome a lot of them, through hard work, but the prevailing notion that anything is possible and all wounds can be healed, just doesn’t ring true for me. Early on in therapy I truly believed I could have a normal life, eventually, if I just put in the work, but now I know that, for me, there are some milestones that will never happen, and some wounds that will never heal, and the scars will be a part of me for the rest of my life. So far, this inability to take on the yoke of Torah, the obligation of daily rituals like wearing a tallit, is one of those unhealed wounds. It’s still possible that, one day, there will be comfort in wearing a tallit of my own, where I can create my own cocoon of time with God, but I’m not there yet.

But there is comfort in seeing so many women around me embracing their beautiful tallitot, and wearing them with pride and ease. On Yom Kippur, the longest day of the Jewish liturgical year, tallitot are worn starting from Kol Nidre, the evening service, through the next morning and afternoon and on through Neilah, the final service of the long day, at sunset. And multiple times during that long day we sing the Yevarechecha, the priest’s prayer, repurposed as a prayer for community. We drape our arms over the people on either side of us, many using their tallitot to wrap their neighbors and loved ones in a communal tent of peace. And it really is beautiful.

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my Young Adult novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?