When I was eight years old or so, I started going to Saturday morning services in the big sanctuary at my Conservative synagogue. Most of the children in our synagogue went to junior congregation on Saturday mornings, for an hour of prayers and trivia games, meant to fit in between morning cartoons and afternoon gymnastics or computer classes. My brother and I went from the short children’s services in the tiny blue sanctuary, to the long adult services in the cavernous, stained-glass spectacle of the big sanctuary. And we loved it, or at least I loved it. The prayers were more complex, the congregants were happier to be there; but, for me, most of all, there were the harmonies.

Harmony, like this.

We had a female Torah reader, along with our male cantor, who sat with us in the congregation, except for when she had to go up to chant the Torah. When I was older, she taught me how to chant from the Torah for my Bat Mitzvah, and taught me the different chant for the Haftorah, and for the reading of the Megillah on Purim, but every week, during Saturday morning services in the big sanctuary, she taught me that there was such a thing as harmony. I learned by singing along with her, and somehow it made the songs sound deeper, and truer, and more complete. More than thirty years later I still sing her harmonies without a second thought.

This year, I finally sang with the choir at my synagogue, as an alto, during the High Holidays. The fasting and prayer and atonement, and the endless standing, of the long day of Yom Kippur is meant to be the final lap of the marathon; the gasping, I-don’t-know-if-I’ll-survive, final effort to change course before the rest of the year begins. But it’s not the repentance, or the fasting, or the standing that makes Yom Kippur powerful for me. In fact, if it were only that I would feel dimmed and darkened by the holiday. No, it’s the communal effort of it all, and the way we create energy and joy together, all of us participating – singing, reading, opening the ark, dressing the Torah, carrying it; for some, just the act of coming into the sanctuary to be with the community for hours at a time.

We read poetry and prose during the services at my synagogue, to dig into the crevices and corners of the prayers that we might otherwise ignore as we push our way through the service. This year we read part of an essay by a Reconstructionist Rabbi named Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, called Soul-AR Eclipse, about how we absorb so much of our loved ones that when they die they don’t totally leave us. I believe this. I’ve taken in so much from the people around me, some good for me, some not so good, but they’ve become so much a part of me that even when they are far away, they seem close by.

Butterfly

Dina

And I think that’s what happened this year as I was singing with the choir. This woman who hasn’t been in my life for many years, was standing right next to me, even singing through me. I felt like an eight-year-old again, singing harmonies, and filled with awe for the music, and the all-of-us. So many years ago she taught me that music can connect us, and help us to express the all-of-it, not just the happiness or the devotion, but everything we feel and can’t find any other way to say. I couldn’t name the feeling at the time, but I felt such relief singing those harmonies, knowing that music could be a conversation, even within myself.

Towards the end of Yom Kippur I went up onto the bima to read a poem by Linda Pastan. I didn’t know why I’d chosen that poem, except that it was one of the shorter readings available, until I read the last lines to the congregation and finally heard the words fully:

“When my griefs sing to me

From the bright throats of thrushes

I sing back.”

And I realized, yes, that’s what I do. I sing back. I sing in conversation with grief. I sing in response to grief. No matter what, I sing. And I’ve been doing it for a very long time.

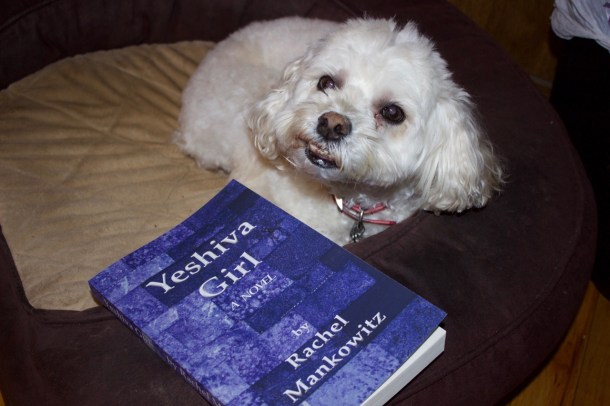

Cricket sings too!

If you haven’t had a chance yet, please check out my Young Adult novel, Yeshiva Girl, on Amazon. And if you feel called to write a review of the book, on Amazon, or anywhere else, I’d be honored.

Yeshiva Girl is about a Jewish teenager on Long Island, named Isabel, though her father calls her Jezebel. Her father has been accused of inappropriate sexual behavior with one of his students, which he denies, but Izzy implicitly believes it’s true. As a result of his problems, her father sends her to a co-ed Orthodox yeshiva for tenth grade, out of the blue, and Izzy and her mother can’t figure out how to prevent it. At Yeshiva, though, Izzy finds that religious people are much more complicated than she had expected. Some, like her father, may use religion as a place to hide, but others search for and find comfort, and community, and even enlightenment. The question is, what will Izzy find?